Alice Dunbar-Nelson

A poet, author, activist, educator, and philanthropist who spent her career trying to improve the quality of Black Americans’ lives.

1875-1935,

Wilmington, DE

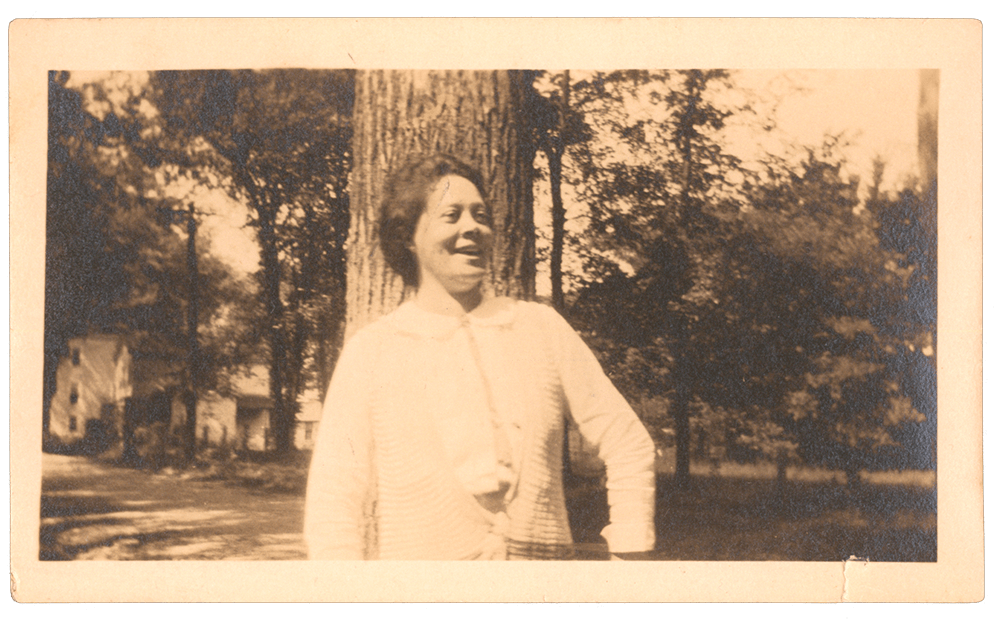

Alice Dunbar-Nelson was a middle-class biracial, queer woman who held many identities within herself at the turn of the twentieth century. She was a poet, author, activist, educator, and philanthropist who spent her career trying to improve the quality of Black Americans’ lives. She was one of the only African American women diarists of the early twentieth century who wrote about the realities of her life as a working-class Black woman. Much of her social commentary and activism remain relevant today.

Despite facing a plethora of obstacles in life, including intimate partner violence, police violence, and continual racial and gender discrimination, Alice Dunbar-Nelson fought for equality and taught future generations how to think critically, appreciate literature, and uplift Black history.

Dunbar-Nelson was born as Alice Ruth Moore in New Orleans, Louisiana, in 1875, among one of the first generations of free Black people after the Civil War. Her ancestral background included African American, Native American, and European American lineages. Her mother, Patricia “Patsy” Moore, was born into slavery in Louisiana around 1850 and, as a single parent, provided educational opportunities for all her children.

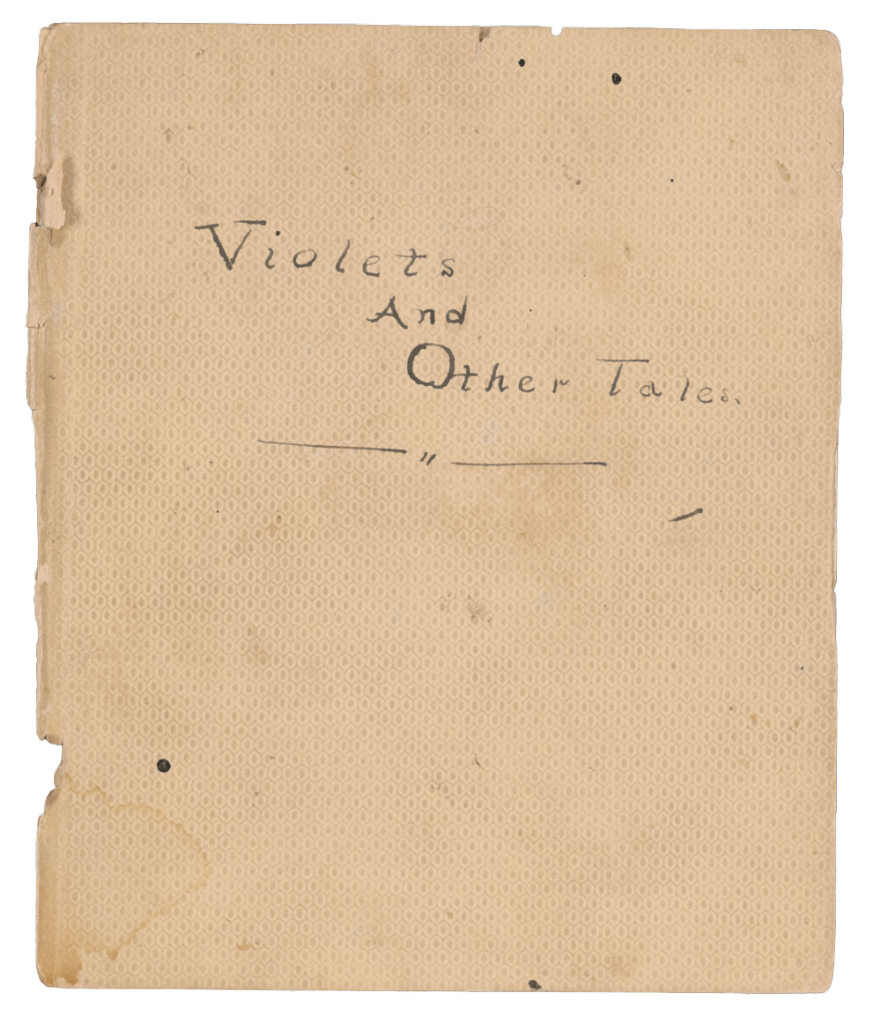

The queer connection to variations of the color purple stems from the ancient Greek poet Sappho, whose work only survives in fragments today. Her poetry included many references to violets as well as romance and erotic verses, particularly related to desiring women. Queer people, particularly lesbians, would come to adopt variations of purple—such as lavender and violet—as a Sapphic cultural symbol pertaining both to Sappho and women being romantically attracted to other women.

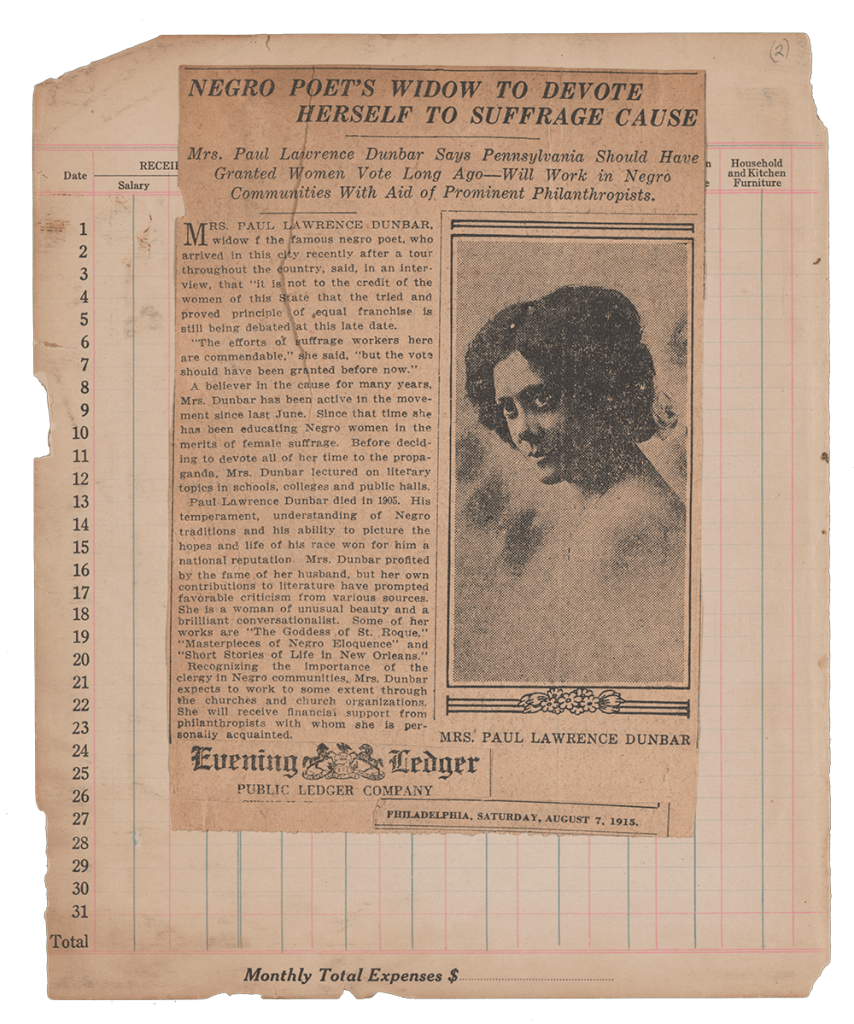

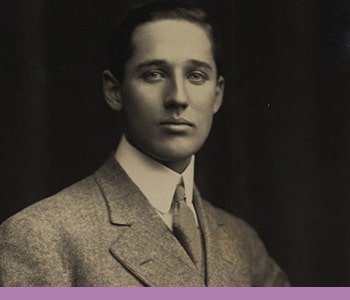

In the late 1890s, Dunbar-Nelson moved north to Boston to pursue her writing career. In 1897 in New York City, she helped run the children’s education program at White Rose Mission settlement house for young Black women. Then, after years of corresponding with the Harlem Renaissance poet, Paul Laurence Dunbar, the two married in 1898. He was a physically and sexually abusive husband, and was likely jealous about the same-sex affairs Dunbar-Nelson (at this time known as Alice Dunbar) wrote about in her diaries. During their marriage, Dunbar-Nelson was forced to abandon her teaching career, a reflection of the late-nineteenth century’s social expectations of women, particularly for a Black, married woman. She left her husband in Brooklyn, New York, in 1902 after he beat her so violently that she had to be treated in a hospital. They never legally divorced, but Dunbar died a few years later in 1906, effectively ending the marriage. Despite the abuse, Dunbar-Nelson often promoted herself as the widow of Paul Laurence Dunbar and became a strong advocate for his literary work, which allowed her access to many spaces she may have otherwise been prevented from entering.

After leaving Dunbar in 1902, Dunbar-Nelson moved to Wilmington, Delaware. There, she got a job teaching at Howard High School, which at the time was the only high school in Delaware for Black students. At Howard High, Dunbar-Nelson prepared her students to think critically and speak articulately. She served as the head of the English department from about 1910 until 1920 while also serving as director of the summer sessions for Black teachers at the State College for Colored Students (now Delaware State University). Dunbar-Nelson not only incorporated classical literature into the curriculum, but also highlighted works of Black authors and included Black history in her courses. Dunbar-Nelson took a year off in 1907 to study British literature at Cornell University and returned to Delaware in 1908. In 1910, she married Arthur Callis, a professor at Howard University; however, they divorced only a year later.

While working at Howard High, Dunbar-Nelson began a long-term relationship with the principal, Edwina Kruse (1848-1930), a biracial woman who was twenty-seven years her senior. Kruse, originally from Puerto Rico, moved to Delaware in 1864 to establish schools in rural districts of southern Delaware. Letters between Dunbar-Nelson and Kruse serve as evidence for the women’s loving relationship. From 1907 to 1911, the women exchanged letters, sometimes multiple times a day, discussing mundane daily tasks and expressing their affection for each other. Not only was Dunbar-Nelson and Kruse’s relationship important for the women personally, but their companionship was significant because of how they formed networks of education throughout Wilmington in the early twentieth century. Through their day jobs, the two women are known for creating a community of Black excellence at Howard High.

In the early twentieth century, it was not uncommon for middle-class Black women to form romantic or sexual relationships. Despite having to keep the relationships secret, and also frequently being engaged in heterosexual marriages, women like Dunbar-Nelson and Kruse found community and love with each other before the terms “bisexual” or “queer” existed with the meanings they have today.

From 1913 to 1914, while continuing to teach at Howard High, Dunbar-Nelson also served as an editor and writer for the A.M.E. Review, published by the African Methodist Episcopal (A.M.E.) Church. By 1916, Dunbar-Nelson was married to her third husband, Black journalist, Robert Nelson. He learned of her “lesbian affairs” after reading her diary, but there is no evidence he responded negatively to the information he discovered on those pages. Throughout her diary entries, Dunbar-Nelson often speaks—quite casually and naturally—about romantic relationships with women, while in her outward life she maintained the cover of being in a heterosexual marriage.

In 1920, Dunbar-Nelson was fired from her teaching job at Howard High for engaging in “political activity” and “not being a team player,” largely in response to her decision to take leave from work to attend an anti-lynching rally in Marion, Ohio. She was a vocal advocate against racist lynchings and in support of women’s suffrage, both controversial topics at the time to support, especially as a woman. Dunbar-Nelson had served as a field organizer for the women’s suffrage movement since 1915. In 1918, she served as a field representative for the Women’s Committee of the Council of National Defense. During World War I (1914-1918), she helped promote the military service of Black soldiers through her literary works, where she discussed the deep sacrifice of African American men who were drafted to serve in a war despite discriminatory conditions.

In 1924, she began teaching at the Industrial School for Colored Girls in Marshallton, Delaware, an institution co-founded in 1920 by herself, Kruse, and the Federation of Colored Women. It is during this time that Dunbar-Nelson writes in her diaries about her intimate relationships with other women, including journalist Fay M. Jackson of Los Angeles and Bermuda-based artist Helene Ricks London.

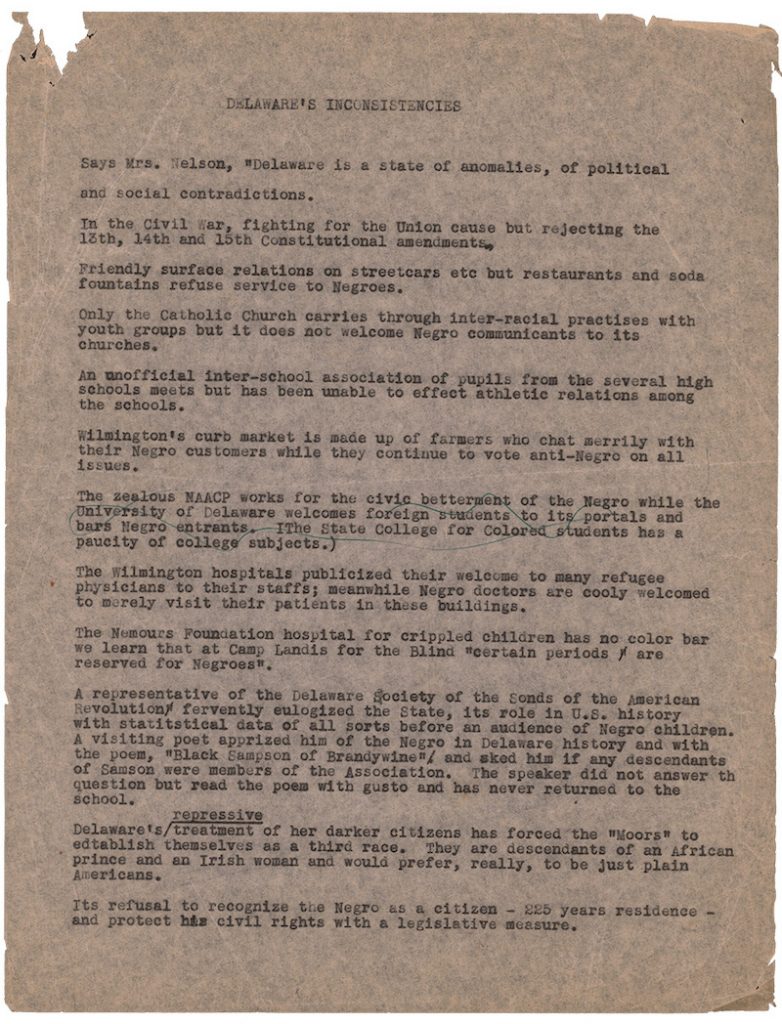

Dunbar-Nelson’s social justice activism was prolific and extended across the country for over two decades. From 1920 to 1922, Dunbar-Nelson and her journalist husband, Robert Nelson, published the Wilmington Avocate, a Black, progressive newspaper focusing on Wilmington’s Black community. From this time onward, Dunbar-Nelson maintained an active career as a journalist, writing for local and national publications. Her writing style combined social commentary with humorous wit. In an undated document titled “Delaware Inconsistencies,” Dunbar-Nelson writes:

Delaware is a state of anomalies, of political and social contradictions. In the Civil War, fighting for the Union cause but rejecting the 13th, 14th and 15th Constitutional amendments. Friendly surface relations on streetcars etc but restaurants and soda fountains refuse service to Negros… Delaware’s repressive treatment of her darker citizens has forced the ‘Moors’ to establish themselves as a third race. They are descendents of an African prince and an Irish woman and would prefer, really, to just be plain Americans.

In 1920, Dunbar-Nelson became the first Black woman to serve on the State Republican Committee of Delaware. In 1922, she helped defeat a sitting United States Senator from Delaware, Dr. Caleb Layton, after he refused to vote for the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill. As part of the campaign, Dunbar-Nelson organized a voter registration drive that added 12,000 new voters to the polls. Layton lost his seat by 7,000 votes. In 1924, she worked to pass the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill, which was blocked from passage in Congress by southerners holding tight to racist sentiments.

Dunbar-Nelson struggled financially for most of her adult life as she sought the funding needed to travel and publish her work. She relied on various jobs and royalty checks from publications, but the systemic racism and sexism of the time made achieving economic stability a challenge for Dunbar-Nelson as a middle-class, Black woman.

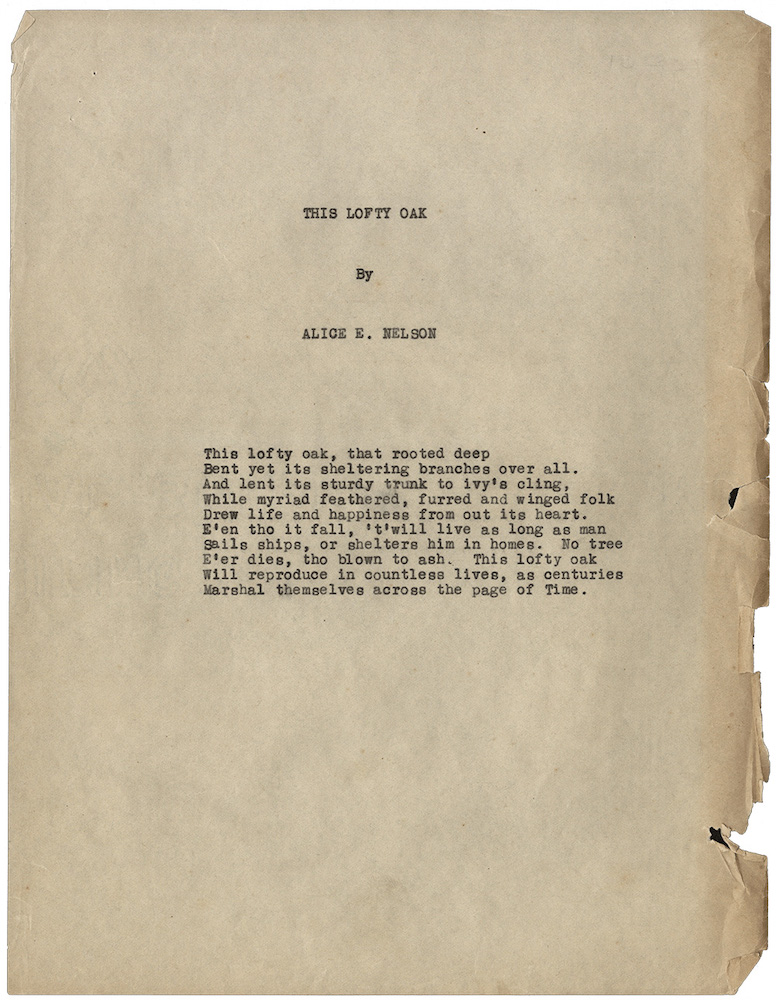

After Kruse’s passing in 1930, Dunbar-Nelson authored a novel, This Lofty Oak, about her lover, Kruse, although it’s difficult to say how much of the novel is true and what is fictionalized because so little is known about Kruse’s life. It was Dunbar-Nelson’s dying wish to have the novel published, but despite all of her achievements in the literary fields, publishers refused to print This Lofty Oak. Kruse’s letters and the unpublished manuscript for This Lofty Oak were purchased by the University of Delaware Special Collections in 1984 and serve as important archival evidence of queer love between two women of color in early twentieth century Delaware.

Dunbar-Nelson moved to Philadelphia in 1932 when her third husband took a job with the Pennsylvania Athletic Commission. At the time, Dunbar-Nelson worked for the American Interracial Peace Committee, from 1928 until 1932. By 1932, her health had begun to deteriorate. In 1935, she died of heart disease at the age of sixty. Her ashes were later scattered over the Delaware River.

While Dunbar-Nelson kept a diary for much of her adult life, the only entries that survived are from 1906, 1921-1922, and 1926-1931. Her queer relationships became public when her diary was published in a 1985 book titled, Give us Each Day: The Diary of Alice Dunbar-Nelson, edited by Gloria T. Hull. Dunbar-Nelson’s personal papers were preserved and cared for by her niece, Pauline Young, who, in 1991, donated many of them to the University of Delaware Special Collections Library. Dunbar-Nelson is only the second Black woman to have a book-length diary published.

Photo Courtesy: University of Delaware Special Collections & Museums

Sources:

- Alice Dunbar-Nelson papers, University of Delaware Special Collections

- “Alice-Dunbar Nelson papers help connect past to the present,” YouTube video posted February 21, 2020 by Delaware’s Government Information Center

- “Alice Ruth Moore Dunbar,” Dayton Aviation Heritage National Historical Park, National Park Service

- “A Love Deeper Than Friendship,” I Am an AMERICAN! The Authorship and Activism of Alice Dunbar-Nelson virtual Rosenbach Museum Exhibition, webpage dated 2020

- Green, Tara, Love, Activism, and the Respectable Life of Alice Dunbar Nelson, (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2022)

- Hollingsworth, Dr. Reba R., “Commentary: Female Black educators in Delaware paved the way,” Delaware State News, June 2, 2022

- Hull, Gloria T., Give Us Each Day: The Diary of Alice Dunbar-Nelson, (W W Norton & Co Inc., 1986)

- Miller, Grace, “An Unsung Legacy:The work and activism of Alice Dunbar-Nelson,” Unbound, Smithsonian Libraries and Archives blog, posted March 12, 2020

- “Voices of Change: A Podcast Inspired by Alice Dunbar-Nelson,” I Am an AMERICAN! The Authorship and Activism of Alice Dunbar-Nelson virtual Rosenbach Museum Exhibition, webpage dated 2020

Explore Other Delawareans

-

Louisa Carpenter

Wilmington and Rehoboth Beach, DE

An equestrian, socialite, and amateur aviatrix who endured a dramatic lesbian love life.

-

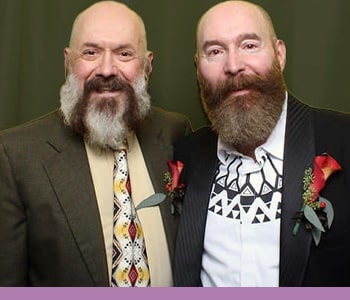

Ivo Dominguez Jr. and James C. Welch

Wilmington, DE

Queer activists and founders of the Gay and Lesbian Alliance of Delaware and the Delaware Lesbian and Gay Health Advocates.

-

Edward Bringhurst III/V

Wilmington, DE

An amateur photographer, antique collector, and dog breeder who embraced a queer identity behind closed doors.

-

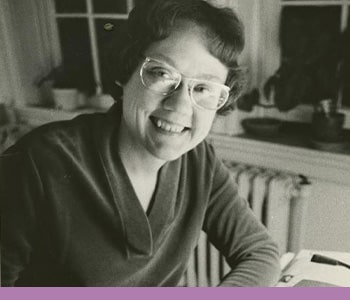

Barbara Gittings

Wilmington, DE

One of America’s most impactful and iconic lesbian activists.