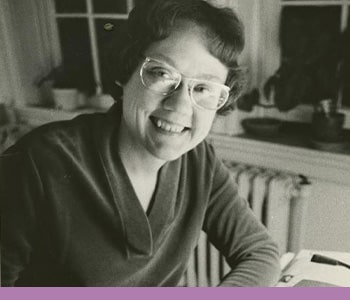

Louisa Carpenter

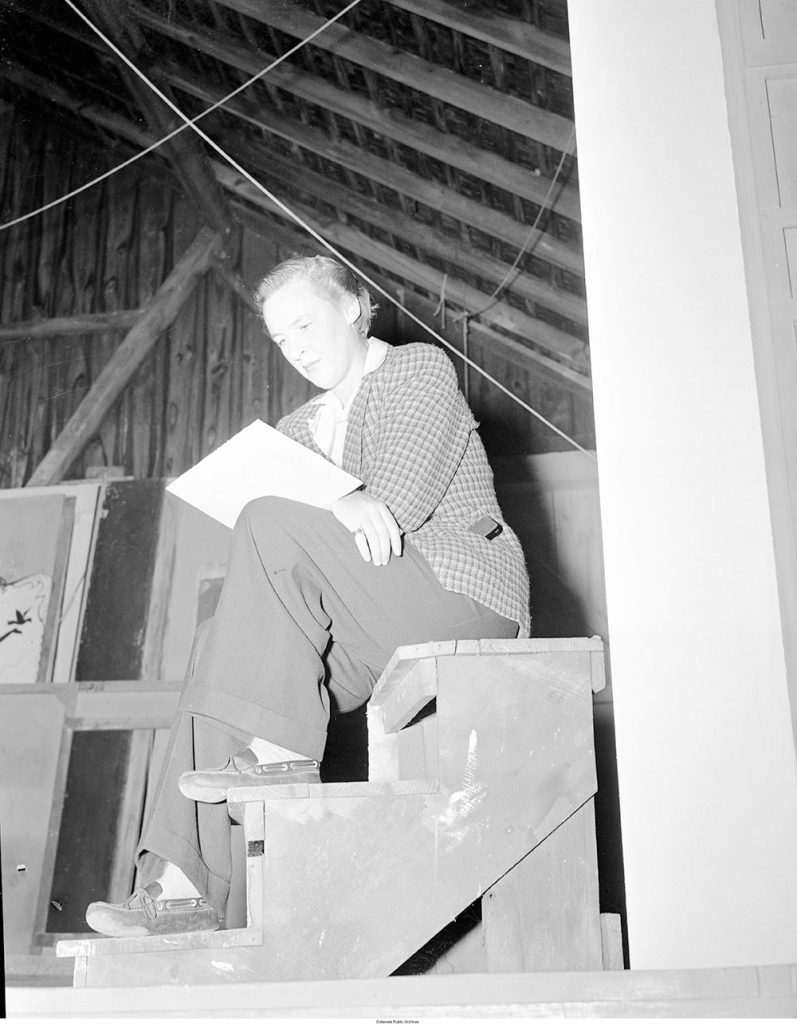

An equestrian, socialite, and amateur aviatrix who endured a dramatic lesbian love life.

1907-1976,

Wilmington and Rehoboth Beach, DE

Louisa Carpenter, a descendent of the du Ponts, defied gender norms and had relationships with women in the early twentieth century. She utilized her family’s immense wealth to throw private parties where many queer, and often closeted, people gathered at her family home in Rehoboth Beach. She is often cited as the woman who first introduced a queer sensibility to Rehoboth.

Delaware native Louisa D’Andelot Carpenter suffered immense heartbreak during her sixty-eight years of life, but offered many of her queer friends and admirers the chance to be themselves when many others did not.

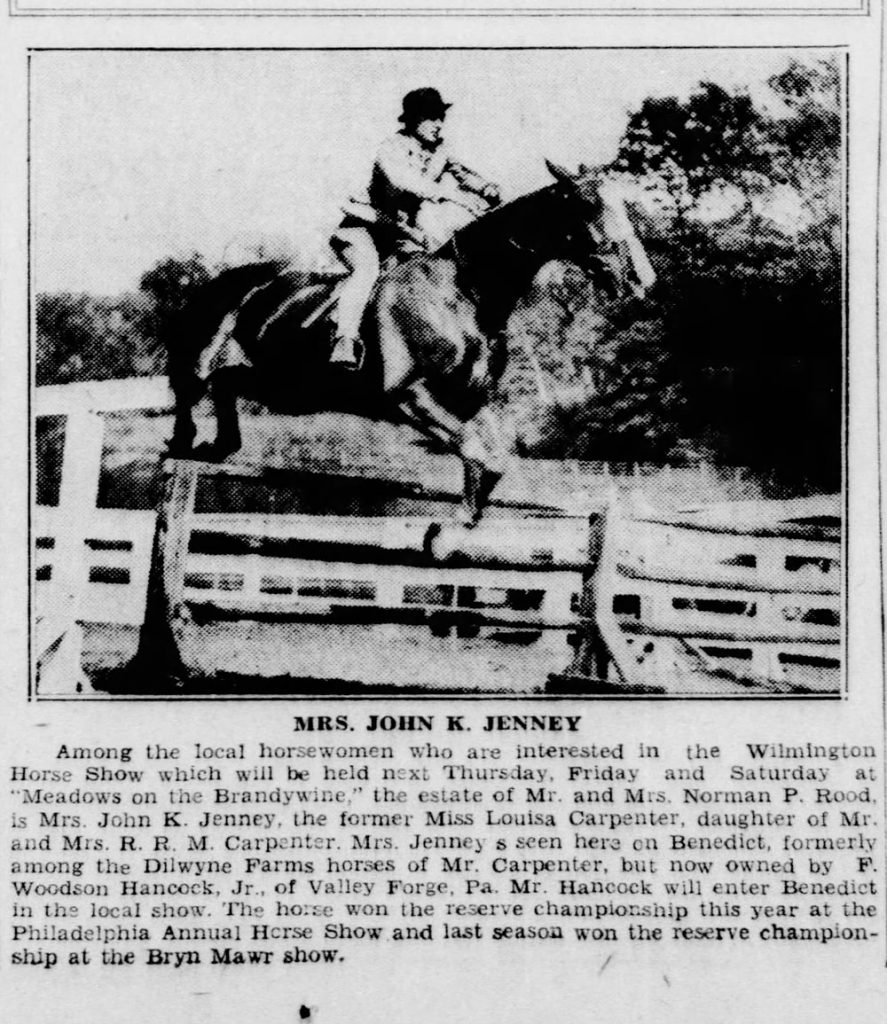

Carpenter was born on October 7, 1901, in Montchanin, Delaware, to Robert R.M. Carpenter Sr. (1877-1949) and Margaretta du Pont (1884-1973), making her the great-great-granddaughter of Éleuthère Irénée (E.I.) du Pont de Nemours, the founder of the DuPont industrial empire. Louisa Carpenter was the eldest child and was described in a biography about Libby Holman, her future lover, as a “tall, beautiful, strawberry blonde” when she was twenty-two years old. She grew up a “country girl,” hunting foxes, pheasant, and doves. She rode horses, fished, and drove tractors, which is remarkable not only because of her social status, but because these activities were usually reserved for men in the early twentieth century.

In July 1929, at the urging of her parents, Louisa Carpenter married John Lord King Jenney, a DuPont executive. During their marriage, the couple largely lived apart. Carpenter wanted to be a mother, but when she became pregnant, she miscarried.

In a biography about Holman, it’s noted that Carpenter “tried to be an acceptable wife but she despised the role,” one that she had agreed to in order to “please her mother and escape her father’s house.” According to local lesbian author, Fay Jacobs, Carpenter and Jenney lived separately even during marriage. Of the short-lived union, Jacobs said, “While Louisa was married to DuPont executive John Lord King Jenney in 1929, it was open knowledge that the socialite and aviatrix was interested in Sapphic romance.” The marriage ended quickly and they divorced in 1931.

Before, during, and after her brief marriage, Carpenter spent a lot of time in New York City, expanding her passion for theater by attending plays. She aspired to be a theatrical producer, but she did not like the city life, so she traveled back and forth between her family home in Wilmington, Delaware, and New York City.

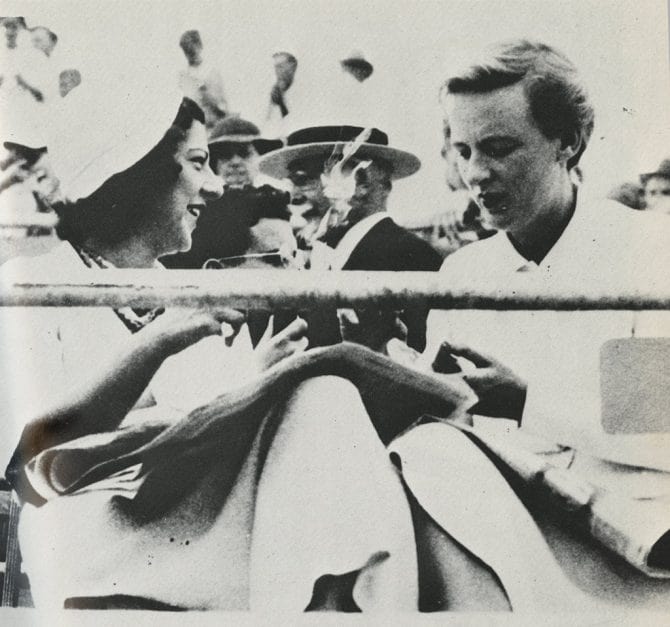

At the time, bisexuality was fashionable and common among the Jazz Age theatrical crowd in New York City. Carpenter was first introduced to her longtime partner, Broadway singer Libby Holman (1904-1971), by film star Clifton Webb at an international horse show in Manhattan. The following night, Louisa Carpenter waited for Holman “outside the stage door of the Music Box Theatre in her chauffeur-driven limousine.” The next weekend, she invited Holman to sail aboard her father’s yacht. By the end of 1929, Carpenter and Holman were inseparable and Carpenter often traveled to Harlem to visit Holman’s favorite clubs and watch her performances. However, Carpenter preferred the weekends the couple spent at her home in Montchanin, Delaware, or on her yacht.

Starting in the 1930s and well into the 1950s, Carpenter hosted her friends, many of them queer, at the Carpenter mansion in Rehoboth Beach. The two artistic communities of Broadway and Hollywood were heavily intertwined, and movie stars like Greta Garbo and Tallulah Bankhead were recorded socializing at the Carpenter mansion. Jacobs wrote of these gatherings in her novel Fried and True:

A large field on the periphery of town doubled as a small airfield to allow celebrities to swoop in and out for private gay weekends. According to reports of those who were there, it was a very cultured, very sophisticated scene and tradition that continued for years.

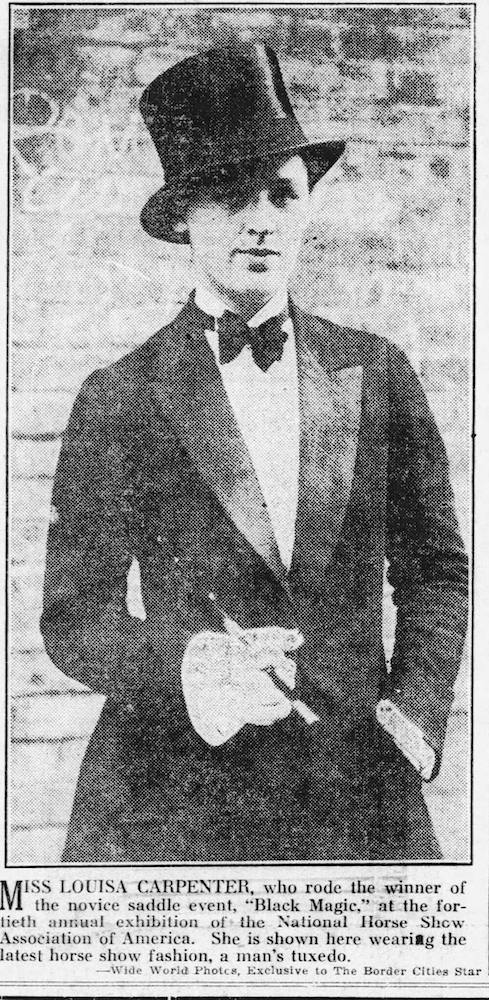

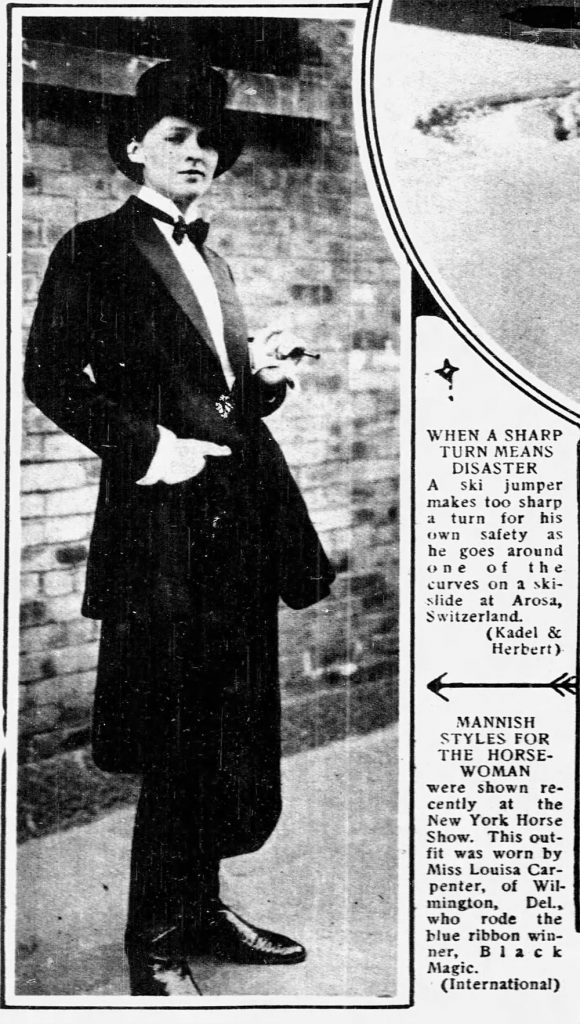

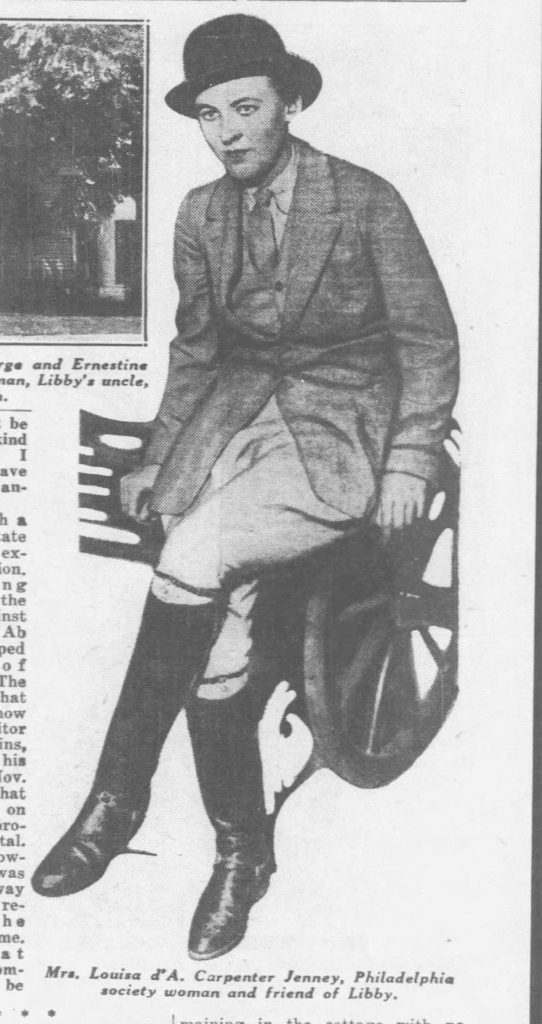

One of Libby’s friends, Helen Lynd, called Carpenter a “he-she.” She is quoted as saying, “Who is that person? She walks like a man, she talks like a man. God, she even dresses like a man.” Carpenter was known to wear what were traditionally considered men’s clothes, and she used her familial wealth to generously spoil the bisexual women she had relationships with.

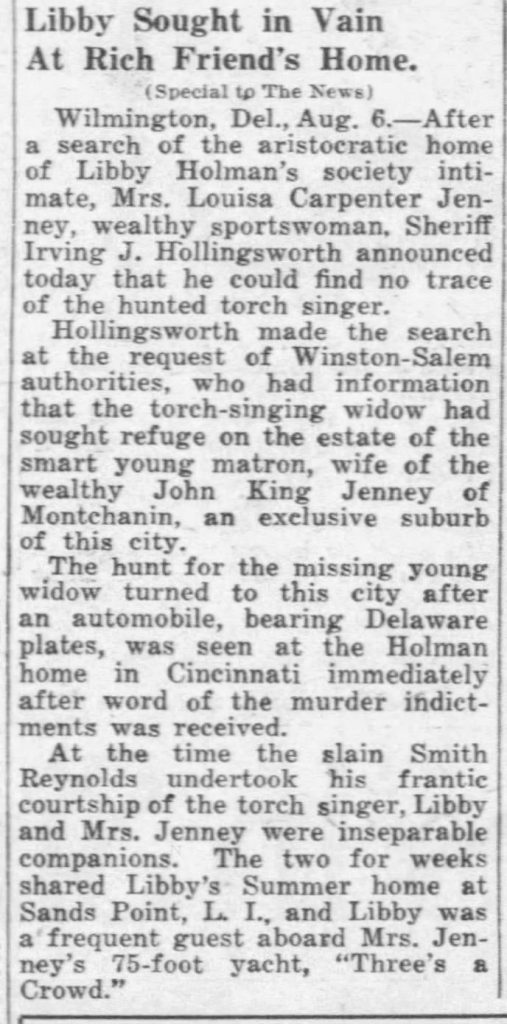

Holman and Carpenter made national headlines when, in 1932, Holman’s husband, Smith Reynolds, suffered a gunshot wound to the head. Holman claimed he committed suicide, but the police investigated Holman’s possible involvement in his death. At first, Holman was not charged with the murder, and traveled to be with her family in Wyoming. Holman, expecting to remain in Wyoming, was surprised when, on July 14, 1932, Louisa Carpenter’s black Cadillac showed up at their family home.

Holman left with Carpenter, heading to Carpenter’s house in Montchanin, Delaware, to avoid press and the police. On August 4, 1932, a North Carolina grand jury indicted Holman for the murder of her husband, but she was nowhere to be found. Knowing of Holman and Carpenter’s “close friendship,” authorities were mobilized in Delaware to find her.

Montchanin then became too obvious to be a hiding spot and Carpenter assigned Bill Broadwater, the chief engineer on her father’s yacht, to help conceal Holman. Following the indictment, Broadwater brought Holman to the Carpenter family’s 345-acre farm property, known as “the cabin,” hidden in the woods in northern Delaware. Holman was then hidden on another Carpenter property in Maryland before she finally turned herself in to authorities on August 5, 1932. North Carolina police did not possess sufficient evidence to support the charge for premeditation in the alleged murder, so Holman was released on bail. Carpenter, donning a mink coat, paid Holman’s $25,000 bail that August so she would not have to wait behind bars for a trial. The case was eventually dismissed. While hiding from authorities, Holman revealed that she was two months pregnant with the child of her late husband.

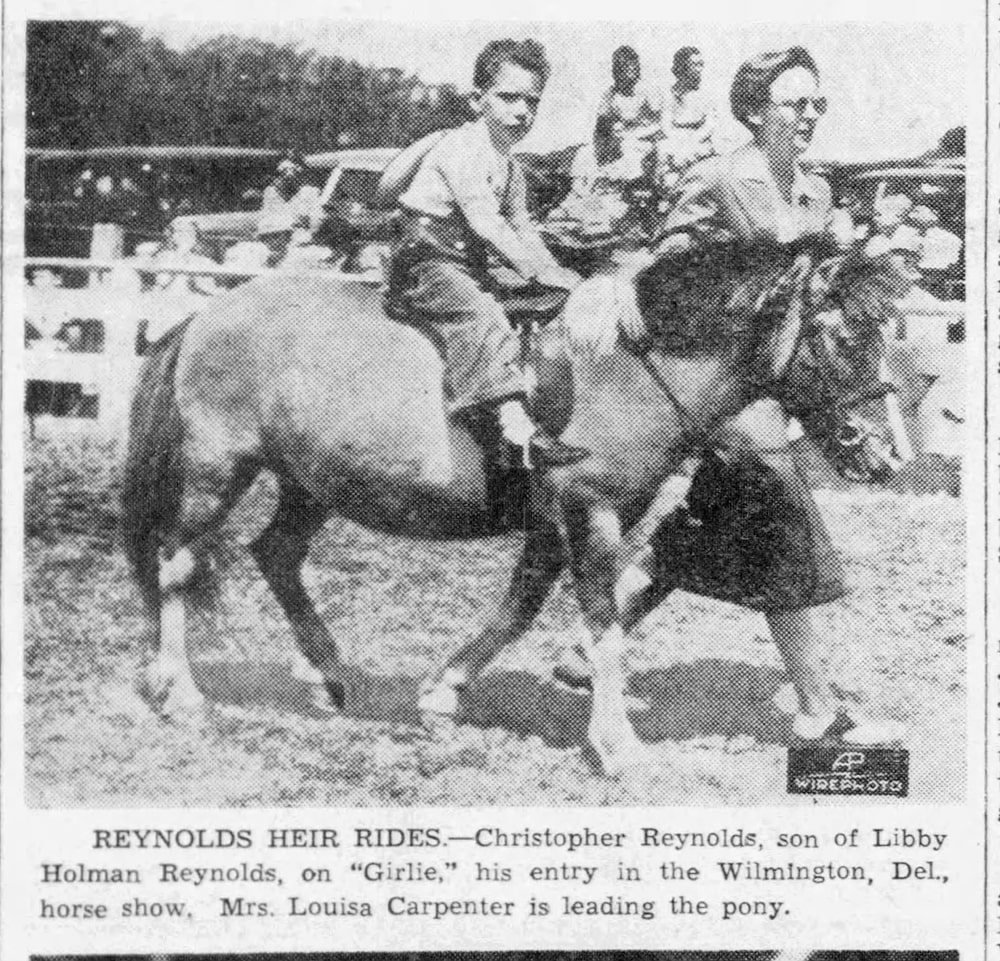

On December 13 of that year, Holman rented a home for the winter near Owl’s Nest Road in Christiana Hundred where she was joined by her mother and frequently visited by Carpenter. For the next month, Carpenter drove Holman to Pennsylvania Hospital in Philadelphia for routine examinations during her pregnancy. On top of being pregnant, Carpenter told a local newspaper that Holman was suffering from a “nervous breakdown.” On January 10, 1933, Holman gave birth to a boy she named Christopher Smith Reynolds, and Holman and Carpenter raised the child together.

Carpenter and Holman lived together at the Montchanin estate in what became known as a “Boston Marriage,” indicating they were romantic friends who trusted and depended on each other. At this point in their relationship, after being together for several years, raising a child, and overcoming dramatic events in their lives, their love had grown far deeper than just sexual intimacy. Among their theater friends, the women were accepted as a perfectly normal couple. Some people snickered, particularly those vying for Carpenter’s attention, but Carpenter continued to host large gatherings of rich, young socialites, novelists, playwrights, and more, members of what she called her “Sapphic circle.”

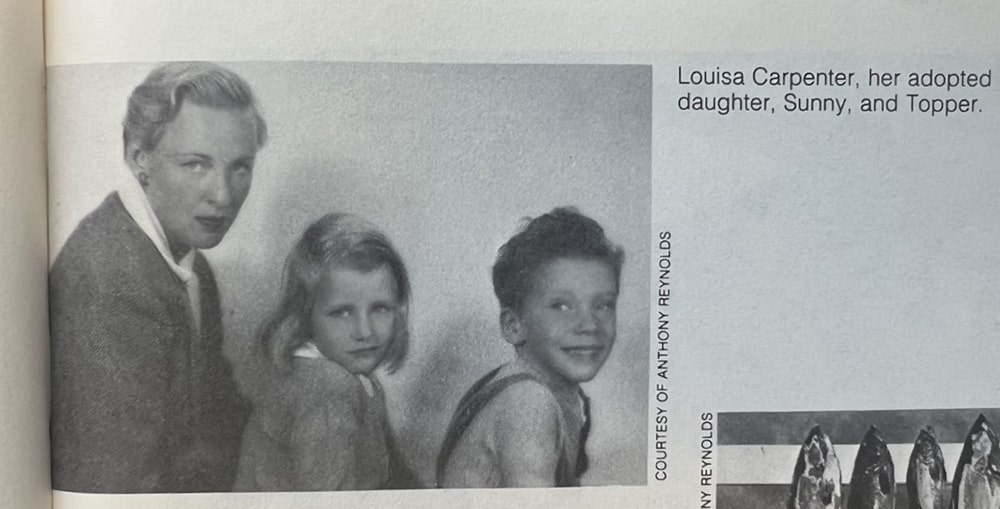

After Christopher Reynolds, who they called “Topper,” turned eighteen months old, Carpenter wanted to adopt a little girl his age so he could grow up with a sibling. Carpenter and Holman visited Philadelphia orphanages, looking for their little girl. Carpenter found a little blonde girl she would call Sunny (1932-2019), short for Sonia, and adopted her into the family. They grew up surrounded by Carpenter and Holman’s friends, their “lesbian and homosexual uncles and godfathers.” A 1950 federal census indicates that by this time, Carpenter was living separately from Holman and had adopted two more children, Carla (b.1938) and Ronald (b. 1935).

In addition to raising their children, Carpenter spent the 1940s through 1960s on philanthropic efforts in the tristate area, including turning her 243-acre property near Chestertown, Maryland, into a summer camp for children with disabilities through the Delaware Society for Crippled Children and Adults in 1955. In 1942, she managed the Robin Hood summer theater in Arden, Delaware, because she believed theater could bolster the morale of the public during World War II. In 1948, Carpenter moved to Springfield Farm in Kent County, Maryland, where she housed her extensive collection of horses. It also was here that she established the Springfield Foundation to work toward building housing for low-income families in the county.

Tragically, in 1950 at the age of seventeen, their son Topper died in a mountain-climbing accident, when he froze to death while attempting a climb of California’s Mount Whitney with a friend. After enduring repeated tragedies (the tragic loss of her first husband and son, as well as the overdose death of her second husband in 1945), Holman never recovered from the grief, and eventually took her own life in 1971.

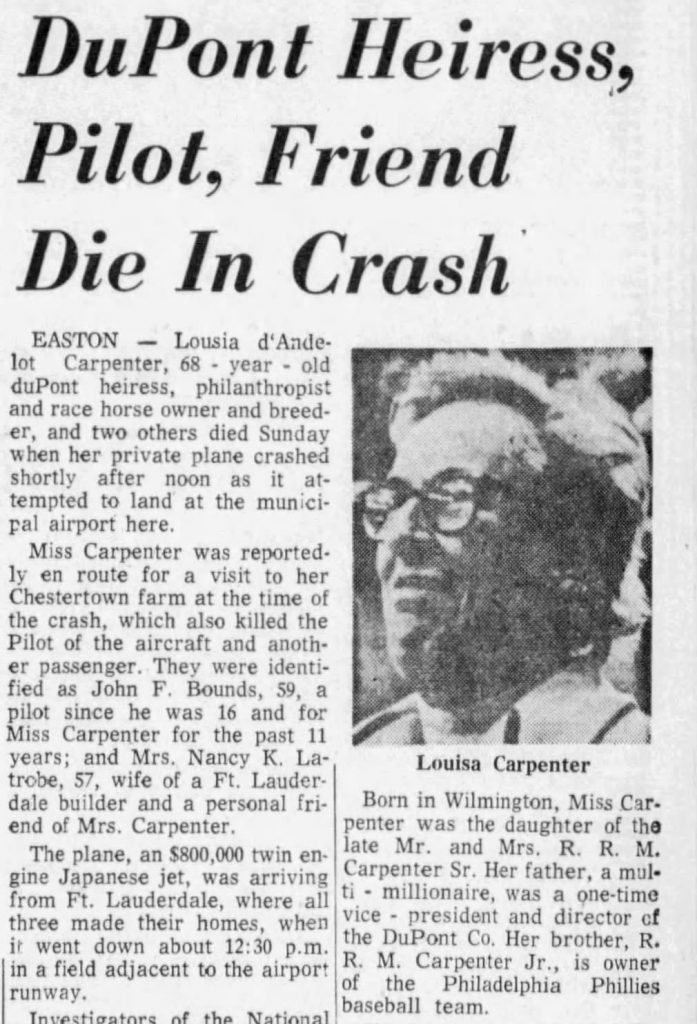

After Holman’s passing, Carpenter continued to host friends at her family’s Rehoboth Beach home. She also invested hundreds of thousands of dollars into horses and horse racing, as she was interested in horses since she was a young girl. Carpenter, an amatuer aviatrix (female pilot), owned an $800,000 twin-engine Japanese jet that she used to travel between her home in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, and her farm near Chestertown, Maryland. Tragically, in 1976, she died in a plane crash a few miles away from her Maryland home. Carpenter was a passenger in the plane when it crashed, killing Carpenter, the pilot, John F. Founds, and Carpenter’s friend Nancy K. Latrobe.

Carpenter’s parties for queer people in the late 1930s marked the beginning of more and more queer people vacationing in Rehoboth Beach. In the 1950s through the 1970s, hundreds of queer people would gather on the beach in front of the Carpenter mansion, which was far enough away from the main Boardwalk and Rehoboth Avenue area that closeted queer people could still enjoy themselves in relative anonymity.

Rumor has it that, in the early 1980s, gay men got tired of hauling their beach chairs all the way past the Boardwalk and began gathering on a beach just north of the Carpenter house. This area became the unofficial “gay beach” – now dubbed Poodle Beach. In December 2020, a historic marker was approved to honor this area where queer people have historically gathered for community and relaxation. As of June 2023, the marker was in progress but not yet installed.

Photo Courtesy: Delaware Public Archives, Rehoboth Art League Archives., Libby Holman: Body and Soul by Hamilton Darby Perry, Daily News New York, Dreams That Money Can Buy: The Tragic Life of Libby Holman by Jon Bradsaw, Newspapers.com.

Sources:

- Barnett, Rich, “The Du Pont, The Torch Singer, and The Tobacco Heir,” The Go Cup blog, published August 29, 2005

- Bradshaw, Jon, Dreams That Money Can Buy: The Tragic Life of Libby Holman (New York City: William Morrow & Co, 1985).

- “DuPont Heiress, Pilot, Friend, Die in Crash,” The Daily Times, February 9, 1976

- Faderman, Lillian, Odd Girls and Twilight Lovers: A History of Lesbian Life in 20th century America (New York City: Columbia University Press, 1991).

- Flood, Chris, “Century-old Shell House comes down,” Cape Gazette, published August 4, 2020

- Jacobs, Fay, “The Gaying of Rehoboth Beach: Good for all in a town with room for all,” Delaware Beach Life, October 2008

- Jacobs, Fay, “A Wild Part of Our Gay History Is Gone,” Camp Out by Letters to CAMP Rehoboth, published August 12, 2020

- Jacobs, Fay, “Cover Story: Historic Poodle Beach by Fay Jacobs,” Letters to CAMP Rehoboth, published July 16, 2021

- “Libby Holman Suffers Nervous Breakdown in Phila. Hospital,” The Morning Call, January 25, 1933

Explore Other Delawareans

-

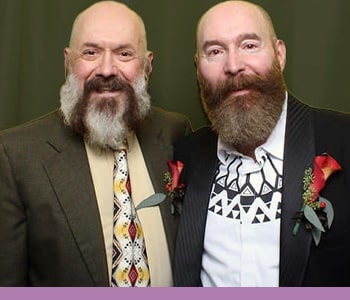

Ivo Dominguez Jr. and James C. Welch

Wilmington, DE

Queer activists and founders of the Gay and Lesbian Alliance of Delaware and the Delaware Lesbian and Gay Health Advocates.

-

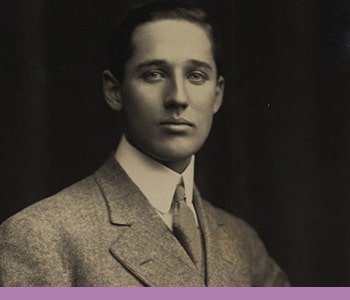

Edward Bringhurst III/V

Wilmington, DE

An amateur photographer, antique collector, and dog breeder who embraced a queer identity behind closed doors.

-

Barbara Gittings

Wilmington, DE

One of America’s most impactful and iconic lesbian activists.

-

Alice Dunbar-Nelson

Wilmington, DE

A poet, author, activist, educator, and philanthropist who spent her career trying to improve the quality of Black Americans’ lives.