Edwina Kruse’s Letters to Alice Dunbar-Nelson

Dozens of letters, some romantic and some mundane, were shared between lovers and colleagues Edwina Kruse and Alice Dunbar-Nelson shortly after the turn of the century.

1907,

Wilmington, DE

A selection of more than 70 letters from Edwina Kruse (1848-1930), Howard High School’s first Black principal, sent to her lover, Alice Dunbar-Nelson (1875-1935), in 1907 shed light on their intimate relationship and details of their daily lives. The letters, as well as a transcript of Dunbar-Nelson’s unpublished novel based on Kruse’s life, were purchased by the University of Delaware Special Collections in 1985 and serve as important archival evidence of queer love between two women of color in the early twentieth century in Delaware.

Edwina Kruse, who served as the first Black principal and one of the first female leaders at Howard High School in Wilmington, not only made her mark on Delaware history as a highly regarded educator, but also for her long-term relationship with Delaware author, activist, and educator Alice Dunbar-Nelson. The long-standing romance between the two women is memorialized in a series of letters shared among one another in 1907.

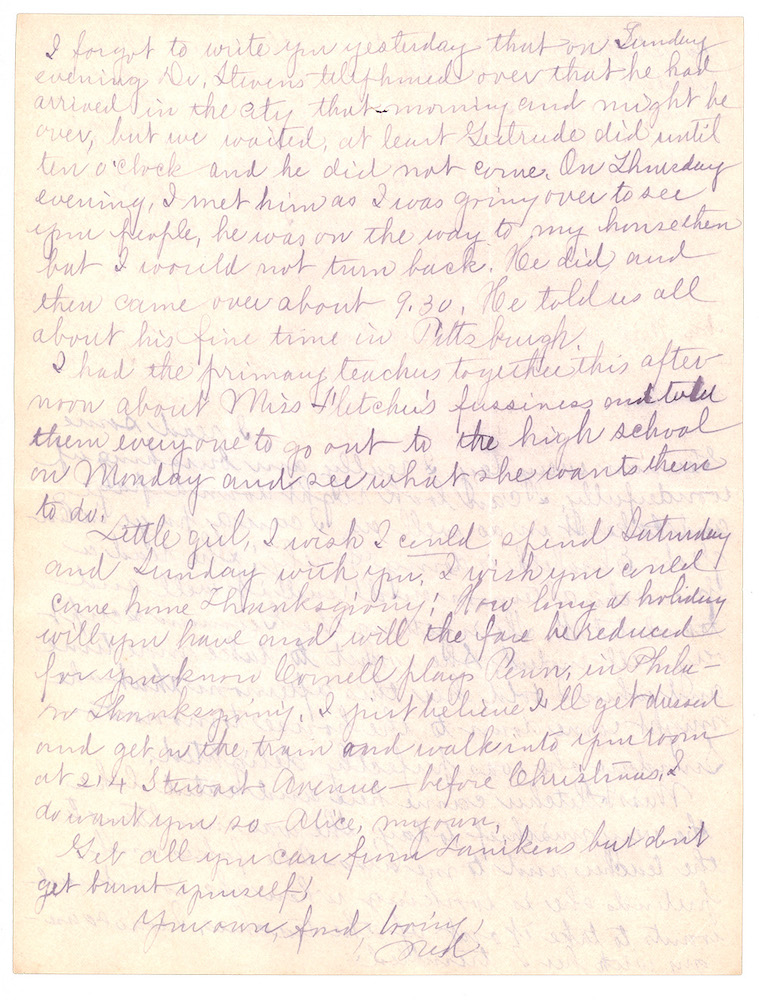

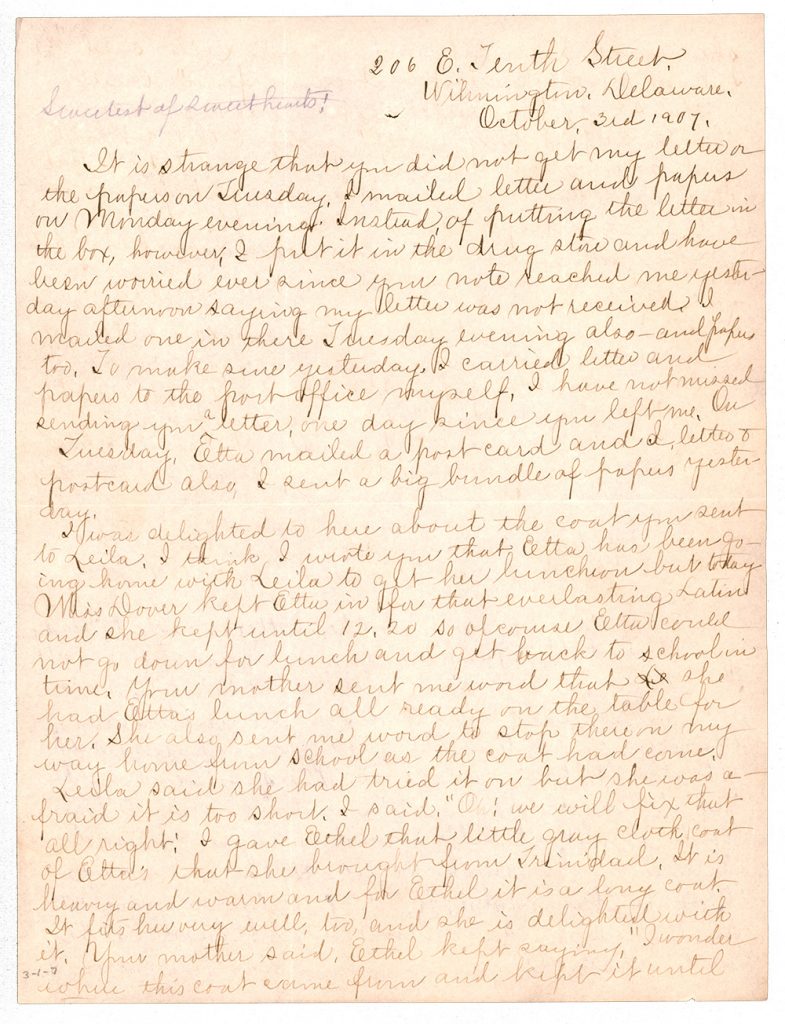

It was during this year that the women exchanged letters almost daily, and sometimes multiple times a day, while Dunbar-Nelson studied British literature at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. Some letters simply shared mundane details of daily life, such as information about family, current events, and school business while others illustrated their love and affection. Letters from Kruse to Dunbar-Nelson often began affectionally with, “my dearest sweetheart,” “my own dearest,” or “my dear kid.” In letters and in Dunbar-Nelson’s own diaries, she referred to Kruse as “Ned,” an affectionate nickname understood between the two women. Kruse also signed her letters from “Ned,” sometimes “with a heart full of love,” or “your own, Ned.”

Author Lillian Faderman, in her book Odd Girls and Twilight Lovers: A History of Lesbian Life in Twentieth Century America, explains that while “romantic friendships” between women have always occurred throughout history, in the nineteenth century with the creation of “separate spheres,” men and women were working in sex-segregated spaces and thus women ended up finding comfort and affection among one another. Education gave women more agency as they were able to leave the house and join the workforce. Working together at Howard High, for example, created an environment for Kruse and Dunbar-Nelson to bond over shared values, intelligence, and attraction. However, the women still had to remain discreet about their relationship and maintain a public appearance of respectability to avoid further marginalization. That idea is also supported in author Tara Green’s Love, Activism, and the Respectable Life of Alice Dunbar-Nelson, in which she writes: “moving within the boundaries of respectability meant balancing discretion and desire.”

Many of the letters were pages long, often beginning with updates on Kruse’s daily activities, which often included looking after Dunbar-Nelson’s mother, Patricia “Patsy” Moore, and sister, Mary Leila Moore Young, as well as her nieces, Ethel Corinne Young and Pauline Alice Young, who all attended Howard High and felt fondly for Kruse. Kruse, who benefitted from investments she made throughout her career, financially provided for Dunbar-Nelson and her family for years. Kruse bought food in bulk, pretending it was only for herself, so that she could share it with the family. On this support, Kruse wrote in an October 22, 1907, letter:

I try to help her [Patsy Moore] because I love you so much, and told you I would look after them, but I have to be careful because she is very proud.

In an October 4, 1907, letter to Dunbar-Nelson, Kruse wrote:

Little girl, I wish I could spend Saturday and Sunday with you. I wish you could come home Thanksgiving: How busy a holiday will you have and will the fare be reduced for you know Carnell plays Penn in Philadelphia on Thanksgiving [?] I just believe I’ll get dressed and get on the train and walk into your room at 214 Stewart Avenue– before Christmas. I do want you so– Alice, my own.

The next day, Kruse followed up, writing: “I want you to know dear, that every thought of my life is for you, every think of my heart is yours and yours alone. I just can not ever let anyone else have you. Your own- own, Ned”

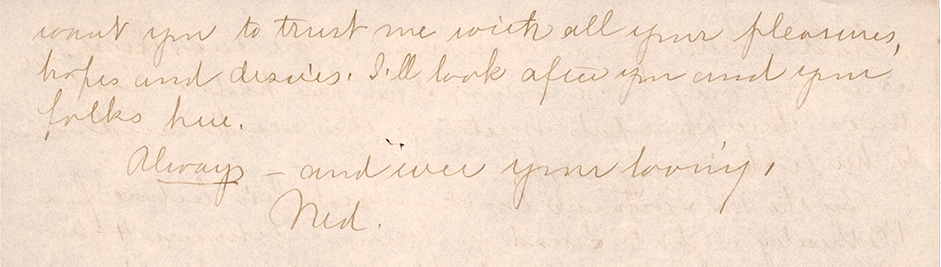

On October 26, 1907, Kruse ended a six-page handwritten letter with, “Trust me with all your pleasures, hopes and desires. I’ll look after you and your folks here. Always- and ever your loving, Ned”

In her letters, Kruse also shows concern for Dunbar-Nelson’s mental and physical health, sometimes reminding her distant lover to take study breaks and not overexert herself. When Dunbar-Nelson returned to Wilmington in 1908 and resumed teaching at Howard High, it was no longer necessary for them to communicate as frequently in writing.

Kruse was originally born in San Juan, Puerto Rico, in 1848, to her German father and Cuban mother and came to the United States in 1852. Her mother died in 1857 and her father died in 1862. Shortly after her parents’ deaths, in 1864, Kruse moved to Delaware. She pursued her education in Massachusetts and Virginia before moving to Wilmington, Delaware, after Howard High School opened in 1867.

Her light skin likely helped her get a job at Howard High School, at first as a teacher under a white principal. By the 1880s, Kruse had begun a decades-long tenure as the highest ranked administrator at Howard High, which at the time was the only four-year school in Delaware that admitted Black students. Through her roles at Howard High, she was known as being generous to her students and ensured countless children received high-quality education to help them pursue further education in college.

Kruse met her future lover, Dunbar-Nelson, when Dunbar-Nelson joined the faculty at Howard High in 1902. While it’s unclear when the two began their intimate relationship, they immediately bonded over their desire to provide excellent education to Black children. The women became closer when Kruse began providing Dunbar-Nelson with financial assistance, including funding Dunbar-Nelson’s year of education at Cornell University. Kruse supported Dunbar-Nelson’s desire to further her education not only because she loved her, but because of the distinction and respect that having the chair of the English department (Kruse promoted Dunbar-Nelson to that position in 1910) educated at Cornell would bring to Howard High.

In the early 1920s, when Kruse was replaced and forced to retire, Dunbar-Nelson wrote an editorial to her as part of her “From a Woman’s Point of View” series in the Pittsburgh Courier, even though they had a falling out that year. The piece did not reveal the details of their personal relationship, but rather praised Kruse’s work as principal of Howard High. Dunbar-Nelson wrote:

To have raised the intellectual standard of a community is no small task, but when you add to that, the enduring monument of a splendid school, the education of thousands of boys and girls, and you have an achievement well worthwhile, and a life that has been finely worth living.

In addition to her impactful career in education, Kruse also was an entrepreneur who owned property and a catering business.

It is unknown when the intimate relationship between Kruse and Dunbar-Nelson ended; however, they maintained a friendship throughout the rest of Kruse’s life. Kruse died on June 23, 1930, and Dunbar-Nelson reflected on her feelings for her former lover in a diary entry, writing:

Krusie [Edwina B. Kruse] died tonight at nine o’clock [of double pneumonia]. Poor dear old Ned-Odduwumuss. My mind goes back over the years from 1902 to 1909 when we were closer than sisters–till first Arthur [Callis], then Anna [Brodnax] broke up our Eden– and then to 1920 with our semi-friendship. Those first seven years!…

Krusie– her life spelled more romance than will ever be told. A friend she was–and paradox of Paradoxes– one of my worst enemies. Let her soul rest in peace. I loved her once. Twenty years ago, her death would have wrecked my life…

Photo Courtesy: University of Delaware Special Collections, Alice Dunbar-Nelson papers, and Delaware Public Archives

Sources:

- Alice Dunbar-Nelson papers, University of Delaware Special Collections

- “Alice-Dunbar Nelson papers help connect past to the present,” YouTube video posted February 21, 2020 by GIC (Government Information Center) Delaware

- “A Love Deeper Than Friendship,” I Am an AMERICAN! The Authorship and Activism of Alice Dunbar-Nelson virtual Rosenbach Museum Exhibition, webpage dated 2020

- Faderman, Lillian, Odd Girls and Twilight Lovers: A History of Lesbian Life in Twentieth-Century America, (New York City: Columbia University Press, 1991)

- Gibson, Judith Y., “Might Oaks: Five Black Educators,” University of Delaware, last updated August 4, 1997

- Green, Tara, Love, Activism, and the Respectable Life of Alice Dunbar Nelson, (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2022)

- Howard High School of Technology booklet, accessed online July 2023

- Hull, Gloria T., Give Us Each Day: The Diary of Alice Dunbar-Nelson, (New York: W W Norton & Co Inc., 1986)

Explore Other Documents

-

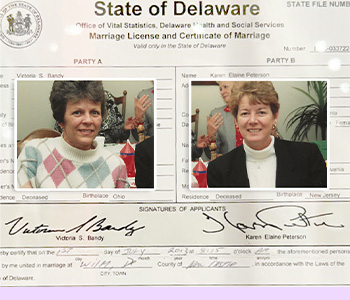

Delaware’s First Same-Sex Marriage License

Wilmington, DE

The marriage license issued to then-state Senator Karen Peterson and her partner Victoria "Vikki" Bandy was Delaware's first same-sex marriage certificate.