History was made here: The Dover Green

By First State Heritage Park Interpretive Programs Manager Ryan Schwartz

Established by William Penn in 1683, Dover is one of Delaware’s most historic cities and The Green — laid out in 1717 according to Penn’s specifications — is the historic heart of that city and a component of both the First State National Historical Park and the First State Heritage Park.

The city of Dover and its historic Green are a part of a rich tapestry of human history. Long before the first cobblestone was laid by European colonists, the lands on Delmarva that would become Kent County were occupied by Native Americans, particularly the Lenapé people. Here they lived in close connection with the land for thousands of years, a lineage so storied that their name for themselves, “Lenapé,” means simply “the human beings.” Indeed, among the members of the East Coast Algonquian peoples, the Lenapé are counted among the elder tribes. Theirs was a sophisticated agricultural society of several language groups and clans — matrilineal and matriarchal — and strongly oriented around the family unit.

By 1600, as European colonists began their own explorations of what is now Delaware, they encountered the Lenapé and their Nanticoke brethren for the first time, Native society had already been deeply impacted by these new arrivals from the Old World. Epidemics and a reluctance to adopt European lifeways often led them to either migrate westward or to “hide in plain sight.” Even as Kent County began to emerge as a part of British North America, the first peoples’ presence was never lost from these lands.

Most of Kent County’s first European colonists did not arrive directly from Europe. Many travelled south from Pennsylvania, of which Delaware was a part, being known as the “Three Lower Counties.” Others, streamed in from Maryland, especially the Eastern Shore. Some of these families — Rodneys, Dickinsons, Killenses and Chews — were drawn to the agricultural potential of Kent County. Tobacco and later wheat and corn would flourish here. They brought with them hosts of enslaved peoples, on whose labors they built their plantations and the economic success of the new county. These prominent families remained among the largest slaveholders in Delaware throughout the colonial period. In fact, the 10 square miles around Dover represented the largest concentration of slaveholding plantations in the colony.

It was amidst this complex backdrop that Dover itself came into being. It grew as many such colonial communities did: by necessity and around a nucleus of taverns and a courthouse. With the growing affluence of the area, it was only a matter of time before the scattering of plantations and yeoman farmsteads required colonial administration that distant New Castle and Lewestown could not provide. Less than a year after assuming control of the Delaware counties, William Penn ordered the establishment of an inland town on the St. Jones River. He named this proposed town “Dover,” after the English port city, and specifically decreed that it would host a courthouse. While this measure may not seem significant today, in the colonial period, the formal establishment of a court in a region marked a critical milestone in its development.

Penn laid out the town according to his particular preferences, crafting an orderly layout of streets and lots on a grid which centered around a trio of open common areas, the most important being the half-acre of bare dirt that would become the Dover Green. It took time for Penn’s vision for the town to become reality — despite his writ, the town remained a small cluster of buildings until 1717 — but it was clearly set up for success. Built on high ground beside the navigable St. Jones River which flowed to the Delaware Bay, and being bisected by the primary land route from Philadelphia to Lewes, the King’s Highway, Dover had all the right ingredients to be a lasting settlement.

The Dover Green was originally known as the Public or Courthouse Square, as it was where that first all-important courthouse was established between 1687 and 1689. It was swiftly joined by taverns like the King George and the more famous Golden Fleece, whose male and female keepers alike provided beer, bed and a bellyful to weary travelers and those on court business. The town grew apace with the county, which attained approximately 5,000 inhabitants (free and enslaved) by 1742. By then, dozens of families had established themselves around The Green. They were of all stripes: working class tradespeople clustered around the taverns to ply their craft while prominent families from surrounding plantations took up townhouses, accompanied by enslaved persons who they used to maintain their lifestyle and whose skills were often rented out to others.

By the mid-1700s, 20 to 25 percent of Delaware’s population was enslaved with few legal rights. Indeed, some of Delaware’s earliest legal discrimination of the basis of race began with the enactment of the first Black Codes, beginning with a law entitled “For the Trials of Negroes” in 1700. These laws, along with the fact that Black lives would be bought and sold along the Dover Green’s margins until the end of the Civil War, made the courthouse and The Green represent something very different to African Americans than the welcoming space it was to their white counterparts.

The lives of all of Dover’s residents — both free and enslaved — mingled on The Green. Here they worked, participated in weekly markets and seasonal county fairs, saw public punishments administered, watched militiamen muster and carouse and, on July 29, 1776, first heard the words of the Declaration of Independence as it was read from the courthouse steps. It proclaimed the idea that all men were created equal and launched not just a war for independence but also one of the greatest moral contradictions in American history. The events of that pivotal year also happened to launch Delaware’s own independence, allowing it to formally break away from Pennsylvania in June. The Green heard the ringing calls for change and felt the crackling heat as the portrait of a once-beloved monarch burned in a bonfire set by former British subjects-turned-American revolutionaries.

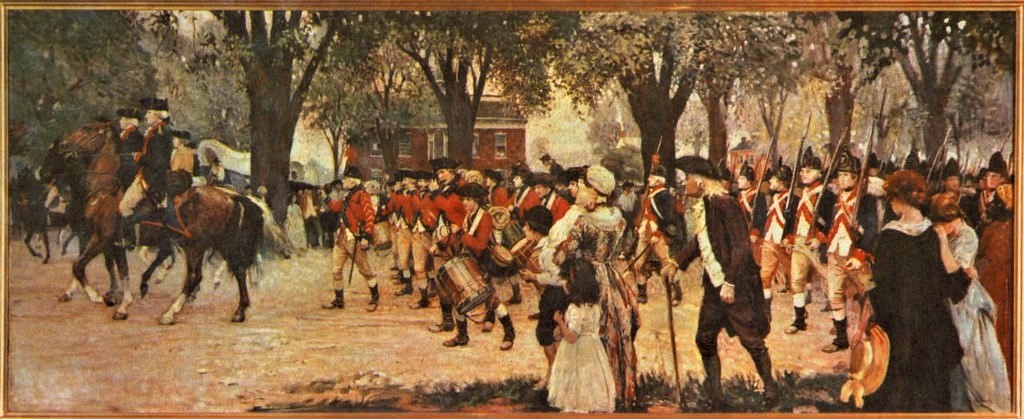

Dover and its Green played a key role in the Revolutionary War. The Public Square’s wide-open space was where the Delaware Regiment, one of the finest fighting units in the Continental Army, was organized in 1776 and where it would muster one final time in 1780 before marching south to glory and near-annihilation in some of the conflict’s bloodiest battles. It became a nexus of intelligence gathering, funneling information from lookouts as far south as Cape Henlopen north to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia. In 1777, with British forces marching to seize that city — and with the Delaware State’s General Assembly under threat and its president (governor) in British chains — the state capital was moved from New Castle to the safer and more centrally located Dover. This move was cemented after the war’s end in 1787 by two key events.

First was the assemblage of 30 prominent white men, 10 each from the three counties, in the meeting room of the Golden Fleece Tavern. There, they convened for just five days to debate the merits of the newly-proposed United States Constitution which they formally ratified on behalf of the Delaware State on Dec. 7. Delawareans mark that date to this day as Delaware Day, remembering it as the moment where their state undertook an important role in the forging of American nationhood and claimed a moniker for all time: the First State.

Second, construction began on an impressive Georgian-style structure on the eastern side of The Green, built to house Kent County’s offices and the court. An offer was extended to the state government to share the building, which was accepted, and the first meeting of the state legislature took place in what is now known as The Old State House in 1791. The building served as the home of the Kent County courthouse until 1873, and as the seat for state government until 1933 when the General Assembly re-located to its new home in Legislative Hall. The halls and ornate staircase of The Old State House represent both the grandeur of the American experiment, where a new government rooted in enlightenment ideals was born and evolved, and the contradiction of a land where equality was subject to skin color and a man’s freedom could be auctioned on the building’s front steps.

Listed individually in the National Register of Historic Places in 1971 and designated as a National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom site by the National Park Service, The Old State House is operated as a museum by the Delaware Division of Historical and Cultural Affairs. For reservations and information about free tours and special programs, contact the museum at call 302-744-5054 or OSHmuseum@delaware.gov.

As the 19th century dawned, Delaware and Dover took their places in a new American republic. Families came and went, technologies advanced and the town became a city outstripping William Penn’s margins. Governments also changed, crime and punishment were administered, often unequally, and wars were waged, including a terrible Civil War that would end race-based chattel slavery in America.

Throughout the 19th- and 20th-centuries, The Green continued to bear silent witness to events great and small including everyday people demanding that the promises at the heart of America’s founding be made true for everyone — from the trial of Underground Railroad conductor Samuel Burris in The Old State House to suffragists campaigning for gender equality; from Civil Rights activists striking against Jim Crow to Native Americans reasserting themselves on their ancestral soil. In that tradition, The Green remains a space for assembly, dialogue and learning just yards from the modern seat of government in the First State.

Today, visitors to Dover find in The Green a tranquil oasis, surrounded by fine buildings and shaded by stately trees contributed by Victorian-era Doverites. Little do many realize the stories that this truly historic half-acre has to tell, legacies and lessons just waiting to be revealed.

The Green is the core component of the Dover Green Historic District which was added to the National Resister in 1977. The historic district encompasses 79 contributing buildings including several located directly on The Green. Visitors can explore the area on their own or as part of walking tours, lantern tours, historical theatre and other programming conducted by the First State Heritage Park. These must be reserved in advance by calling 302-739-9194 or by emailing TourFSHP@delaware.gov.

After enjoying the sites around The Green, visitors may want to take in several other historical attractions in the greater Dover area including: John Dickinson Plantation, Johnson Victrola Museum, Air Mobility Command Museum, Biggs Museum of American Art, Delaware Agricultural Museum and Village and the Delaware Public Archives.

Ryan Schwartz is a public historian originally hailing from Mukwonago, Wis. A 2014 bachelor’s graduate of the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater, he has since devoted his career to education and historical interpretation, working for such institutions as the Rock County Historical Society, Wisconsin Historical Society, Children’s Theater of Madison and Philadelphia’s Museum of the American Revolution. Since moving to the east coast in 2017, his particular focus has been on the late Colonial and Revolutionary periods, especially in the Mid-Atlantic region. He has served as the interpretive programs manager of First State Heritage Park since 2019.