Delaware’s Role During World War I

Delaware’s Role During World War I

A Small State Steps Up In The War Effort

Delaware’s Role During World War I

Delawareans were involved in the Great War before the United States entered in 1917. They served in the British or Canadian armed forces and volunteered on medical teams as ambulance drivers, nurses and doctors.

Approximately 10,000 Delaware residents served in the armed forces at home and abroad during World War I, with 43 making the ultimate sacrifice, while an additional 188 were wounded.

Delaware Military Bases

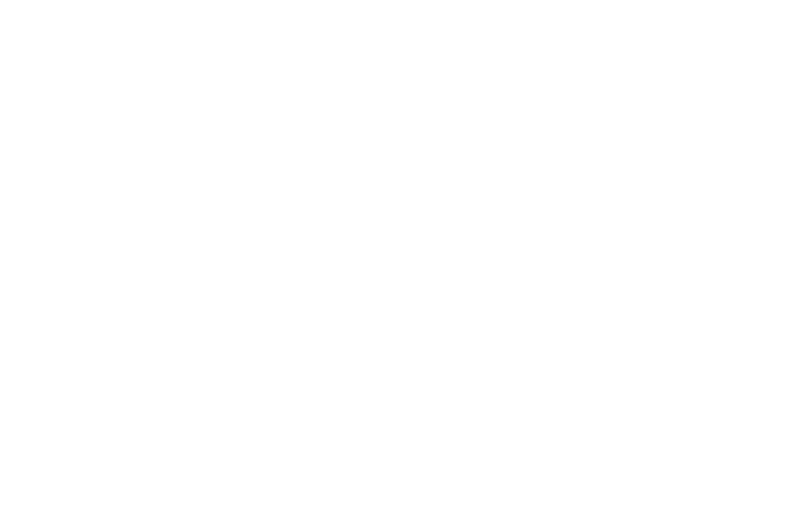

In 1917, the U.S. Navy established large naval bases at Cape Henlopen, Del. and Cape May, N.J. because the areas adjoined the Delaware Bay which could be used strategically to transport men and military supplies to the important shipping ports in Philadelphia, Pa. and Wilmington, Del. To protect the Delaware Bay, the naval base at Cape Henlopen conducted minesweeping activities while the Cape May base patrolled the waterways. Approximately 800 men were stationed at the Cape Henlopen base.

In 1917, the U.S. Navy established large naval bases at Cape Henlopen, Del. and Cape May, N.J. because the areas adjoined the Delaware Bay which could be used strategically to transport men and military supplies to the important shipping ports in Philadelphia, Pa. and Wilmington, Del.

To protect the Delaware Bay, the naval base at Cape Henlopen conducted minesweeping activities while the Cape May base patrolled the waterways. Approximately 800 men were stationed at the Cape Henlopen base.

During 1918, there was German U-boat activity near the naval bases from May until October. The base at Cape Henlopen was closed after the armistice ending the war activities was declared on Nov. 11, 1918

Military Aviation Training

A pioneer in military aviation training, the Delaware Aeronautical Company was founded on June 12, 1917, by Pierre and Irenee S. du Pont and John J. Raskob in order to train pilots for the U.S. government air service. The company was located in Claymont, Del. with 21 men from the U.S. Aviation Corps enrolled in its training classes. The company was in operation for five months, ending on Nov. 30, 1917, in advance of the establishment of government flying schools in 1918. The state of Delaware was a major contributor to aviation training and innovation during the Great War and continues this role today.

The state of Delaware was a major contributor to aviation training and innovation during the Great War and continues this role today.

Delaware Steps Up Production

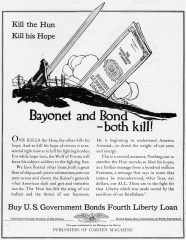

Prior to America’s formal entry into the war, Delaware’s industrial and agricultural production had increased to help supply the Allies and civilians in battle-torn areas. To contribute to the war effort, a number of Delaware companies produced munitions and war-related products. E. I. du Pont de Nemours and Company, headquartered in Wilmington, had over 40 gunpowder and explosives plants throughout the United States. It produced 40 percent of the explosives used by the Allies, including all of the explosives used by the U.S. armed forces. DuPont also produced other war-related products, such as paint for camouflage, adhesives, materials for gasmask eyepieces and chemically coated fabrics for military clothing. Other Delaware companies also contributed munitions, including A. Jedal Company of Newark, Bethlehem Steel’s New Castle plant, Ball Grain Explosives of Wilmington and General Chemical Company in Claymont.

Prior to America’s formal entry into the war, Delaware’s industrial and agricultural production had increased to help supply the Allies and civilians in battle-torn areas. To contribute to the war effort, a number of Delaware companies produced munitions and war-related products. E. I. du Pont de Nemours and Company, headquartered in Wilmington, had over 40 gunpowder and explosives plants throughout the United States. It produced 40 percent of the explosives used by the Allies including all of the explosives used by the U.S. armed forces.

DuPont also produced other war-related products, such as paint for camouflage, adhesives, materials for gasmask eyepieces and chemically coated fabrics for military clothing. Other Delaware companies also contributed munitions, including A. Jedal Company of Newark, Bethlehem Steel’s New Castle plant, Ball Grain Explosives of Wilmington and General Chemical Company in Claymont.

Delaware has a long history of shipbuilding, and the Great War provided additional opportunities for the state’s companies to come to the forefront. Wilmington-based shipbuilding companies Harlan & Hollingsworth and Pusey & Jones produced nearly 90 ships during the war. The Jackson & Sharp Company, also of Wilmington, built grain barges, tugs, ferry boats, towboats and other vessels in addition to rail cars and pontoons. Smaller shipyards also profited from government contracts—William G. Abbott and Vinyard Shipbuilding companies, both of Milford, and John Moore and the Smith and Terry companies, both of Bethel.

Delaware companies also manufactured Bakelite, an early type of plastic used to make gas-mask goggles, produced by Newark’s Continental Fiber, and pontoons and wooden pickets used in bridges and river-bank, supports made by American Car and Foundry in Wilmington.

Delaware’s Agriculture Community Contributes

The rich agricultural resources of southern Delaware provided food for soldiers and civilians.

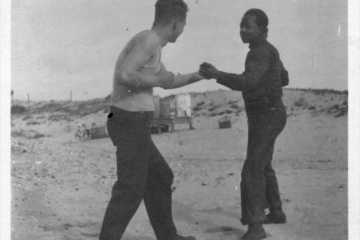

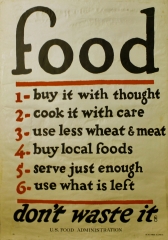

Food production on the American homefront was extremely important, and the U.S. government promoted food-ration programs. Americans learned how to get by with less. The Food Administration initiated “Meatless Mondays” and “Wheatless Wednesdays” as well as “Sweetless” days in order to conserve food resources. Housewives cooked nutritious meals from wartime recipe books. Many Delawareans planted Victory Gardens to provide much of the food for their diets. They also canned, dried and salt-cured their food to prevent spoilage and wastefulness.

Red Cross

Delaware men and women volunteered for the war effort in organizations like the American Red Cross. The Red Cross nurses cared for sick and injured soldiers. They coordinated recreational activities for soldiers stationed both at home and abroad.

German-Americans in Delaware

As the brutal war continued, a wave of anti-German sentiment swept the United States. Recent immigrants with German surnames frequently changed their names. German immigrants were required to register with the federal government and always carry their registration cards. Beginning in 1917, over 2,000 German immigrants were imprisoned throughout the United States.

Some Delaware residents came under increased scrutiny during the war years. Mennonite communities in Delaware were subjected to harsh treatment because of their German heritage. With the nationwide anti-German sentiment, Delaware school curriculums removed German language classes, and books written in German were either banned or burned.

Traditional food dishes with German names were changed. Hamburgers, named for Hamburg, Germany, became Salisbury steak. Frankfurters, the pork sausage named for Frankfurt, Germany, became liberty sausages. Also, the Dachshunds, a dog-breed of German origin, became liberty dogs.

[Not a valid template]Delaware’s National Guard – The 59th Pioneer Infantry Regiment

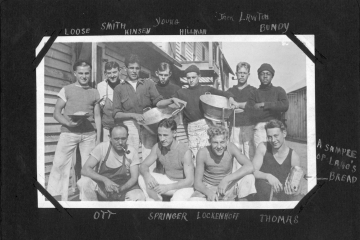

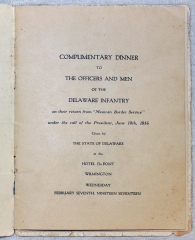

The largest group of Delawareans to serve together in the Great War was in the 59th Pioneer Infantry Regiment, made up of 58 officers and 1,349 enlisted men. For eight months between 1916 and 1917, the regiment, under the command of Gen. John J. Pershing, pursued Francisco “Pancho” Villa along the Mexican border. When war was declared, they were called for service in Europe.

On Aug. 21, 1918, the regiment received embarkation orders to proceed overseas. A few days later, the troops received orders to pack their kits.

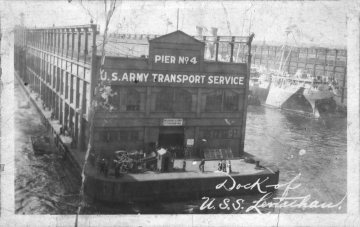

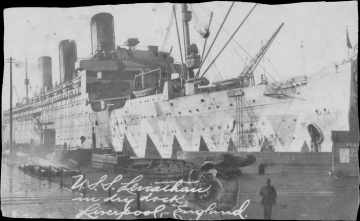

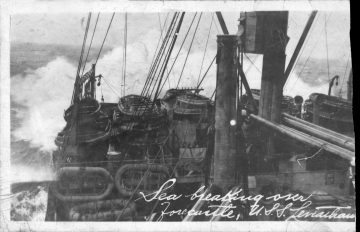

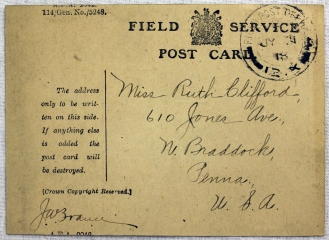

After a grand meal and the provision of two beef sandwiches for each soldier to take along on the trip, the men of the 59th Pioneer Infantry Regiment began their journey from Fort Dix, N. J. late in the evening of Aug. 27, 1918. The 59th sailed from New York Harbor aboard the military ship Leviathan on Aug. 30 and arrived off the coast of Brest, France, on Sept. 7, 1918.

They joined the First Army in the area of Meuse-Argonne and, with French, British and Belgian troops, participated in the largest and deadliest operation that the American military would see in World War I.

Following the armistice on Nov. 11, 1918, the 59th Regiment was assigned the responsibility of salvaging German war supplies, demolition of explosives and operating quartermaster and ordnance depots. The regiment returned home on the Leviathan and was discharged in July 1919.

[Not a valid template]Suggested Reading

- Kennard R. Wiggins, Jr. Delaware in World War I, Charleston, S.C.: The History Press, 2015.

- Kennard R. Wiggins, Jr. “Delaware National Guard in World War I,” “The 59th Pioneer Infantry Regiment,” and “Delaware Military History,” from the Delaware Military Heritage and Education Foundation website.