The U.S. During World War I

The U.S. During World War I

How, Why And When The United States Entered The War

The U.S. During World War I

Although many countries were drawn into the conflict of World War I, the United States maintained a policy of isolationism advocated by President Wilson. Elected in 1912 as the 28th president of the United States, Thomas Woodrow Wilson served from 1913 to 1921. The president vowed to keep the country out of the war, but attacks on American lives eventually made this impossible. On May 7, 1915, a German U-boat sank the British liner R.M.S. Lusitania off the coast of Ireland, killing 1,198 people with 128 Americans among the fatalities.

The president vowed to keep the country out of the war, but attacks on American lives eventually made this impossible. On May 7, 1915, a German U-boat sank the British liner R.M.S. Lusitania off the coast of Ireland, killing 1,198 people with 128 Americans among the fatalities.

President Wilson denounced attacks on passenger ships and repeatedly issued warnings to the Central Powers that the United States would not tolerate unrestricted submarine warfare which was a violation of international law. Germany initially curtailed its attacks, but in January 1917, it resumed unrestricted warfare sinking seven U.S. ships.

Germany also attempted to recruit Mexico to join the Central Powers against the United States by promising financial support to help the Mexicans recover their former territories of Texas, New Mexico and Arizona.

In response to Germany’s actions, President Wilson addressed Congress on April 2, 1917, appealing for the United States to enter the war as “the world must be made safe for democracy.” Four days later, the United States declared war on Germany.

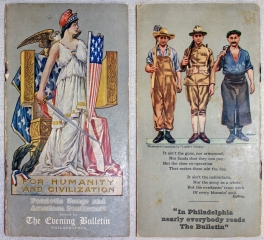

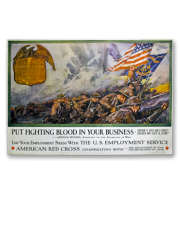

Although President Wilson and Congress saw the need for the United States’ entry into the global conflict, it was necessary to convince the American people of their need to support the war effort. This was not an easy task as the president had won re-election based on his promise to keep the United States out of the fighting. President Wilson and his administration developed a series of propaganda campaigns that focused on the patriotic duty of all Americans to back the war effort in order to defeat the enemy, thus enabling the preservation of democracy at home and abroad. On April 14, 1917, President Wilson established a propaganda organization called the Committee on Public Information (CPI) and appointed George Creel, an investigative reporter and writer, as chairman. The committee remained active until June 30, 1919.

The CPI used multiple forms of media to “advertise” the war. During the years of the Great War, 1914-1919, information and entertainment were communicated through magazines, newspapers, sheet music, silent movies, phonographs, books and posters. There was limited access to radio. Television, computers, internet and social media did not exist. They organized a series of public propaganda speakers across the country, called “Four Minute Men,” to keep Americans informed of the war efforts. The committee published a daily newspaper and produced war films. It also designed educational materials for public schools and universities to energize younger generations to support the United States. The CPI even wrote specific war materials that included suggested prayers for churches and religious institutions.

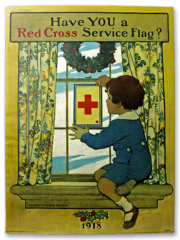

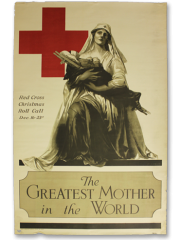

Understanding the power of printed images in the form of posters and cartoon illustrations, Creel recruited Charles Dana Gibson to head CPI’s Division of Pictorial Publicity. One of America’s most popular illustrators and well known for his creation of the “Gibson Girl” image, Gibson employed the best artists, cartoonists and illustrators to produce 1,438 designs for World War I propaganda posters, cards, buttons and cartoons. The Division of Pictorial Publicity was highly recognized for its contribution to the war effort.

A Call to Arms

At the time the United States entered the war, it had a very small, ill-equipped military force. Artists and illustrators designed recruiting posters which flooded the country, enticing men to voluntarily enlist in the service branches. In order to build an adequate fighting force, Congress passed the Selective Service Act on May 18, 1917. This law required all men between the ages of 21 and 30 to register for military duty. By the end of the war, 2.8 million men had been drafted for service.

Posters used patriotic slogans and symbols to inspire Americans to serve their country by enlisting in the military.

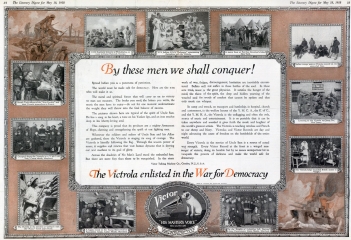

To help prepare American soldiers stationed abroad during the war, pamphlets and booklets containing language translations and information on local currency were issued. The Victor Talking Machine Company developed tutorial foreign-language recordings, including associated translation booklets, to teach French to American soldiers deployed to France.

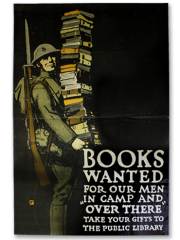

Providing opportunities for entertainment was a way to keep the troops in high spirits. American soldiers craved reading materials and enjoyed listening to music as a means of temporarily escaping the war-time conditions. The American Library Association’s Library War Service maintained libraries for servicemen both in the United States and overseas. In addition to providing a means of diversion, these libraries served to combat low literacy rates, a concern among U.S. military officials. Local book-drives were organized to encourage Americans to donate books for the soldiers’ libraries. It is estimated that between 1917 and 1920, 7 million to 10 million books and magazines were distributed for use by the troops.

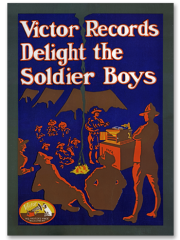

Music played on Victrolas was also a popular pastime, and The Victor Talking Machine Company produced many popular records.

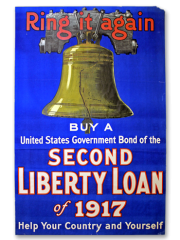

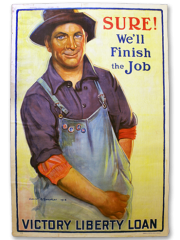

American Liberty Loan Bonds

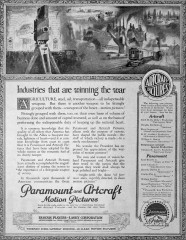

The Wilson administration knew the Great War would come with a large price tag. To generate the necessary funds, Secretary of the Treasury William Gibbs McAdoo created Liberty Loan Bonds. These government bonds paid an interest rate lower than that of banks, but McAdoo utilized propaganda posters drawing on Americans’ sense of patriotism to encourage them to buy the bonds. He enlisted famous artists like Howard Chandler Christy, creator of the “Christy Girl” image, to design patriotic posters, and invited popular actors such as Charlie Chaplin, Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks to participate in bond rallies around the country.

Regardless of their financial means, a high percentage of Americans bought Liberty Loan Bonds. There were also bond campaigns spearheaded by the Girl and Boy Scouts, allowing children to participate in the war effort. During World War I, the American government issued four different Liberty Loan Bonds, while the Victory Liberty Loan Bond was established in 1919 to finish paying war expenses. The United States paid an estimated $32 billion to finance the war.

American Red Cross

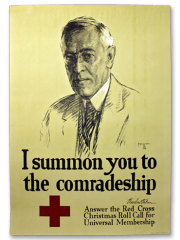

The American Red Cross was founded by Clarissa Harlow (Clara) Barton in 1881 to provide relief to individuals impacted by natural disasters or military conflict. In 1914, the Red Cross sailed the S.S. Red Cross, a relief ship carrying surgeons and nurses, along with medical supplies, to Europe at the beginning of the Great War.

When the United States entered World War I, President Wilson called for all Americans to volunteer and donate funds to help the Red Cross aid soldiers fighting in Europe. To prepare the organization to meet the war efforts, Henry P. Davison was appointed director. Under his leadership, the American Red Cross provided services in Europe to both Allied and American military personnel as well as to civilian war victims.

The American Red Cross was founded by Clarissa Harlow (Clara) Barton in 1881 to provide relief to individuals impacted by natural disasters or military conflict. In 1914, the Red Cross sailed the S.S. Red Cross, a relief ship carrying surgeons and nurses, along with medical supplies, to Europe at the beginning of the Great War.

When the United States entered World War I, President Wilson called for all Americans to volunteer and donate funds to help the Red Cross aid soldiers fighting in Europe. To prepare the organization to meet the war efforts, Henry P. Davison was appointed director. Under his leadership, the American Red Cross provided services in Europe to both Allied and American military personnel as well as to civilian war victims.

To help prepare American soldiers stationed abroad during the war, pamphlets and booklets containing language translations and information on local currency were issued. The Victor Talking Machine Company developed tutorial foreign-language recordings, including associated translation booklets, to teach French to American soldiers deployed to France.

Suggested Reading

- Russell Freedman. The War to End All Wars: World War I, New York: Clarion Books, 2010.

- Evelyn M. Monahan and Rosemary Neidel-Greenlee. A Few Good Women, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2010.

- Robert H. Zieger. America’s Great War: World War I and the American Experience, Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2000.