African-American Participation During World War I

Patriotism Despite Segregation

African-American Participation During World War I

African-American Participation During World War I

Since the first Africans were brought as slaves to the British colony of Jamestown, Va. in 1619, blacks had suffered oppression in the United States first under the American slavery system , and then under the rigid practices of segregation and discrimination that were codified under the “Jim Crow Laws.” With the entry of the United States into the Great War in 1917, African Americans were eager to show their patriotism in hopes of being recognized as full citizens. After the declaration of war, more than 20,000 blacks enlisted in the military, and the numbers increased when the Selective Service Act was enacted in May 1917. It was documented on July 5, 1917 that over 700,000 African Americans had registered for military service. However, they were barred from the Marines and served only in menial roles in the Navy. Blacks were able to serve in all branches of the Army except for the aviation units.

The government made no provision for military training of black officers and soon created segregated training camps for that purpose. Disheartened, blacks protested against this discriminatory practice. Despite the outcry, Fort Des Moines in Iowa became one of the segregated camps and in October 1917 over 600 blacks were commissioned at the camp as captains and lieutenants.

African-American soldiers provided much support overseas to the European Allies. Those in black units who served as laborers, stevedores and in engineer service battalions were the first to arrive in France in 1917, and in early 1918, the 369th United States Infantry, a regiment of African-American combat troops, arrived to help the French Army. Earning the reputation from the Germans as “Hell Fighters,” the 369th was nicknamed the “Harlem Hell Fighters” because the regiment “never lost a man through capture, lost a trench or a foot of ground to the enemy.” The 369th was also the first to reach the Rhine River and provided the longest service of any regiment in a foreign army. They fought in the trenches for 191 days and the entire regiment received the Croix de Guerre medal for their actions at Maison-en-Champagne.

A Black Delawarean at War: One Soldier’s Experience

William Henry Furrowh of Wilmington was drafted into the U.S. Army on Aug. 1, 1918. Like so many African Americans who served during World War I, he was assigned to a segregated labor unit in the American Expeditionary Forces that had joined the British and French troops along the Western Front in France. To record his military experiences, Furrowh wrote brief notations in his diary. His unit sailed for France on Sept. 20, 1918 from the military port in Hoboken, N.J., and arrived in Brest, France on Oct. 1, 1918. He noted that one of his first duties with the Depot Labor Company #23 was to unload flour at the Navy yard.

While serving in France, Furrowh dealt with his feelings of homesickness by writing and sending postcards to his mother, relatives and friends. On special occasions and birthdays, he also mailed beautiful, silk-embroidered greeting cards of a type sold to soldiers. He traveled to several other towns before starting his new military duty on Nov. 2, 1918 at the American ordnance repair shop in Mehun-sur-Yèvre, located in central France. Furrowh’s skilled vocation in the Army was as a pipefitter. After 11 months of service, he returned to the United States and received an honorable discharge at Camp Dix, N.J. on July 24, 1919. In August 1919, he was issued a bronze victory lapel-button for his service.

He traveled to several other towns before starting his new military duty on Nov. 2, 1918 at the American ordnance repair shop in Mehun-sur-Yèvre, located in central France. Furrowh’s skilled vocation in the Army was as a pipefitter. After 11 months of service, he returned to the United States and received an honorable discharge at Camp Dix, N.J. on July 24, 1919. In August 1919, he was issued a bronze victory lapel-button for his service.

Black Medical Officers

Virtually unknown today is the story of 104 African-American medical doctors who volunteered to serve during World War I. They were assigned to care for the wounded and sick in the all-black units of the 92nd and 93rd divisions. Most of these men graduated from the three black colleges that specialized in the training of medical professions: Meharry Medical College in Nashville, Tenn., Howard University College of Medicine in Washington, D.C. and the Leonard Medical School at Shaw University in Raleigh, N.C.

To prepare for their military service, the doctors completed training at the segregated Medical Officers Training Camp at Fort Des Moines in Iowa. Training started in August 1917 and the doctors learned sanitation procedures, camp infirmary work and military medical procedures for combat zones. This rigorous training program was attended by 118 doctors, but only 104 successfully completed the courses to the satisfaction of the Army.

For military service in France, eight doctors were selected out of the 104 African-American medical officers to complete additional medical training at Camp Mead, Md. They left for France in May 1918 and supported the black troops in field hospitals and field artillery.

For military service in France, eight doctors were selected out of the 104 African-American medical officers to complete additional medical training at Camp Mead, Md. They left for France in May 1918 and supported the black troops in field hospitals and field artillery.

The Leonard Medical School produced 13 volunteer doctors who served during World War I. One was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Cross: First Lieutenant Urbane Francis Bass, class of 1906. Under heavy German fire, the Richmond, Va. native made the ultimate sacrifice while aiding wounded soldiers of the 93rd Division’s all-black 372nd Infantry Regiment near Monthois, France.

To learn more about these 104 servicemen, see “Suggested Reading,” below.

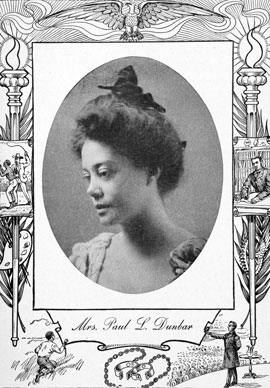

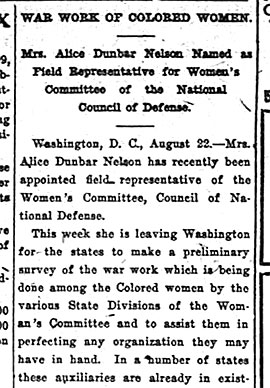

Delaware’s Poet & Activist: Alice Dunbar-Nelson

Delaware poet and activist Alice Dunbar-Nelson and her third husband, Robert J. Nelson, became well known in 1916 for their civil rights activities in Wilmington. During the Great War, Dunbar-Nelson helped to promote the military service of black soldiers through her work as a field representative of the Women’s Committee of the Council of National Defense in 1918. She also used her literary talents to write the play Mine Eyes Have Seen, published in the April 1918 edition of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People’s news magazine, The Crisis. In the play, she discussed the deep sacrifice of African-American men in World War I who were drafted to serve in the midst of discriminatory conditions.

“I’m no slacker when I hear the real call of duty. Shall I desert the cause that needs me? …” Alice Dunbar-Nelson, Mine Eyes Have Seen, 1918

Aftermath of World War I for African Americans

African Americans used the Great War to show their patriotism and to prove they could contribute to the protection and advancement of the country. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People encouraged this spirit of Americanism to counteract racial tension and stereotypes. Because of their valorous service in protecting democracy in Europe, African-American service men began to expect more equality in wages and job opportunities when they returned home. This ideology of advocating for social change and greater respect from white Americans, known as the New Negro Movement, was supported by African-American leaders such as W.E.B. Du Bois, and publicized by black newspapers. Founded in 1917 by Hubert Henry Harrison, a writer, educator and political activist from the West Indies, the movement attracted black writers, poets and activists to openly voice the need for equality.

The New Negro Movement also brought increased social fears and racial tension that erupted in the Red Summer of 1919. Some 25 race riots were reported throughout the country. With the end of slavery and the promises of advancement for African Americans, it was believed at the beginning of the 20th century that white and black people could live in harmony and receive the same opportunities. Reactions after the end of World War I proved the United States had a long way to go in race relations.

African Americans realized they would have to fight for racial equality on all fronts. Racism was even experienced in the suffrage movement when African-American women like Ida B. Wells-Barnett and Alice Dunbar-Nelson supported the need for women’s voting rights. During an organized women’s suffrage march in 1913, the organizers of the National American Woman Suffrage Association asked black women to march separately. Although the 19th amendment was passed to grant the vote to women, it was not until the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s that African-American women could exercise this right without discrimination.

Section Acknowledgments

The Delaware Division of Historical and Cultural Affairs would like to acknowledge the research contributions and kind assistance of the following individuals and organizations during the planning of the “African American Experience & World War I” section:

Leigh Rifenburg, chief curator, Delaware Historical Society, Wilmington

Steven W. Jones, director of development, EbonyDoughboys.org

Curtis Small, Jr., senior assistant librarian and coordinator-public services, Morris Library, Special Collections Department, University of Delaware, Newark

Sylvester Woolford, history and genealogy lecturer

Joseph P. Hickey, researcher, University of Delaware MALS program

Suggested Reading

W. Douglas Fisher and Joann H. Buckley.

African American Doctors of World War I: The Lives of 104 Volunteers, Jefferson, N.C.

McFarland & Company, Inc., 2016.