Shipwreck artifacts undergo months-long desalination process

After decades the final remaining items in a vast collection of artifacts linked to two historic shipwrecks off the Delaware coastline are going through the tedious process of removing salt and moisture so that they can be put on public display.

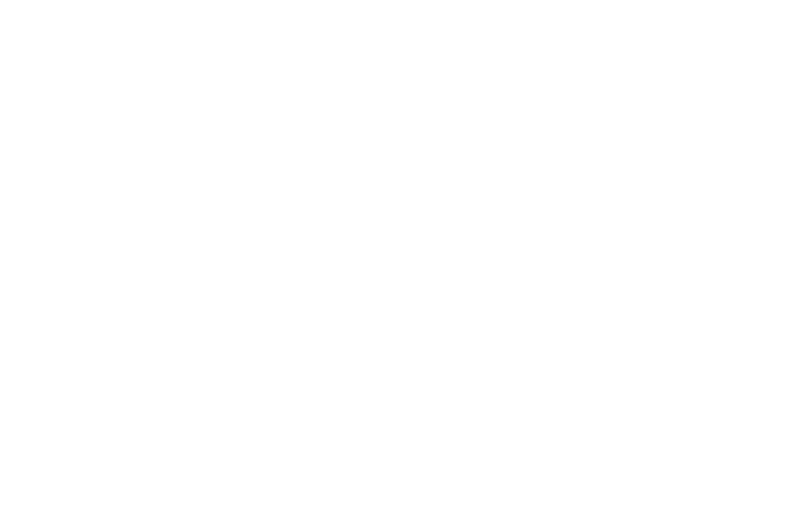

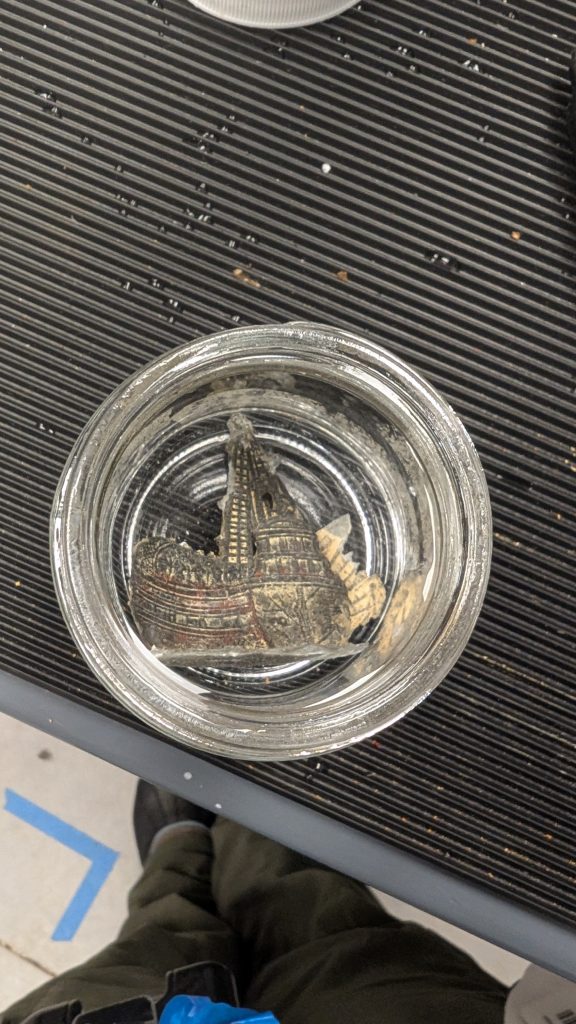

Before the public can lay eyes on a unique collection of everything from wood pieces and ceramic fragments to metal figurines of ships and soldiers, bottles and corks, what appear to be fruit pits, and even miniature dominoes linked to two 18th-century shipwrecks, each item must first undergo a lengthy desalination process by curatorial staff at the Division of Historical and Cultural Affairs (HCA).

The shipwreck items are from the HMS DeBraak, a British ship that sank off the Delaware coastline in 1798, and the Roosevelt Inlet Shipwreck, which is suspected to be of British origin, as well, and to have sunk sometime between 1772 and 1800.

HCA Curator of Archaeology Karli Palmer is overseeing the artifacts’ timely desalination — a process of reducing the salt content from items that have been sitting in high-salinity water from the mouth of the Delaware Bay. If the salt is not first removed before attempting to dry the items, the results could be catastrophic to the integrity of the artifacts.

For the most part, the items only need to have the salt removed so that they can be dried out for public viewing and access. Palmer explained that said shipwrecks and their artifacts actually preserve really well under the water, primarily due to a lack of oxygen (there’s an exception for metal or iron items in saltwater, but that’s a chemistry lesson for another day).

“As soon as you pull them up, artifacts start rapidly deteriorating,” Palmer said. “The salt will basically crystalize and break the object over time.”

While the process of desalination sounds super technical, it’s quite simple. It’s all based on the process of diffusion.

“The idea is you have two solutions,” Palmer said. “If one of them has soluble salts and the other doesn’t, the natural tendency is always for the solutions to balance out.”

By placing the items in distilled water, that need to balance will gradually mean salt is removed from the artifact. As the salt migrates into the distilled water, the water needs to be periodically tested, checked and changed to keep the process going until the water left behind barely has any traces of salt at all.

Palmer measures salinity levels with an electroconductivity meter (the higher the concentration of salt is in a solution, the higher the electrical conductivity will be), and said the ultimate goal is to get the water surrounding the artifacts to reach the same low levels of salinity detected in distilled water. Palmer said the final steps of the process can be different for different materials. Glass and ceramic can simply be dried once the salt is removed, while unique solutions like polymer fills will need to be considered and selected for some of the wood pieces.

“It takes several months of putting an artifact in the water, waiting for it to balance and then changing the water,” Palmer said. “And we just have to do that over and over and over again. Then we can dry it out and put it in the actual collection.”