Stitching together the story of the Kent County girl behind the sampler

How one story sheds light on Delaware’s historical past

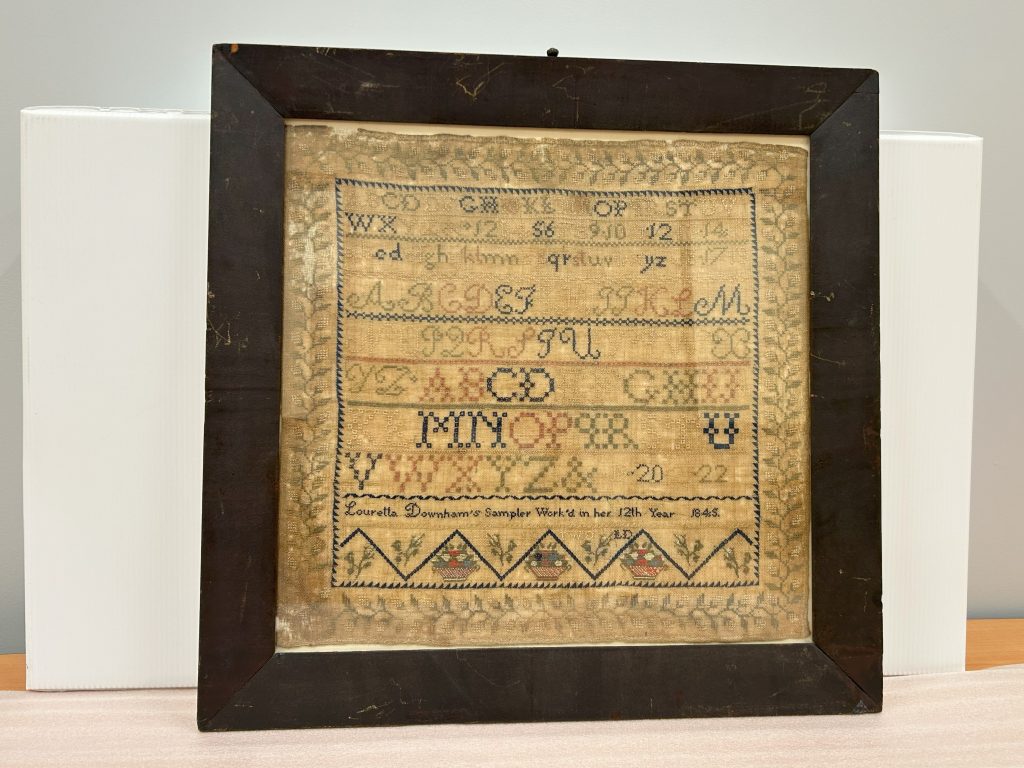

Pictured above is a 19th century sampler from the Division of Historical and Cultural Affairs’ (HCA) collections. It was donated to the state in 1962, with background information including it was created by an indentured servant who had lived with the donor’s great-grandparents. Upon doing additional research, HCA staff discovered pieces of a young life cut short and the social systems that guided it.

This singular item speaks to the larger challenge facing modern-day historians and archaeologists: Piecing together stories of minority populations, including young women, girls and indentured servants. Louretta Downham’s sampler, now in safekeeping by the state, is one example of how a personal story of one Delawarean can shed light on the larger cultural and social structures of the time she lived in.

What is a sampler?

A sampler is a textile on which a girl could illustrate her knowledge of sewing and cross-stitching abilities. They are meant as a “sample” of artistic talent and literacy skills. In a time before modern manufactured textiles, all decorative and practical textile work was done in the home, and thus sewing and stitching skills were considered part of the role of the housewife.

Girls were taught these skills from a young age, and some completed detailed samplers as young as 7 or 8 years of age. There are a variety of samplers in HCA’s collections, and each carries a unique story.

Some records of samplers are been dated as early as the 16th century, and these creative displays were still a part of a young woman’s education into the 20th century. Today, needleworkers still produce samplers to practice and demonstrate their skills, although their cultural context has changed.

Samplers can give historians and others a glimpse into the historical lives of young women, a group that is often overlooked in history. While one sampler cannot tell the entire story of a person’s life, they can provide a material connection to someone whose thoughts and feelings may have otherwise been forgotten to time.

Who was Louretta?

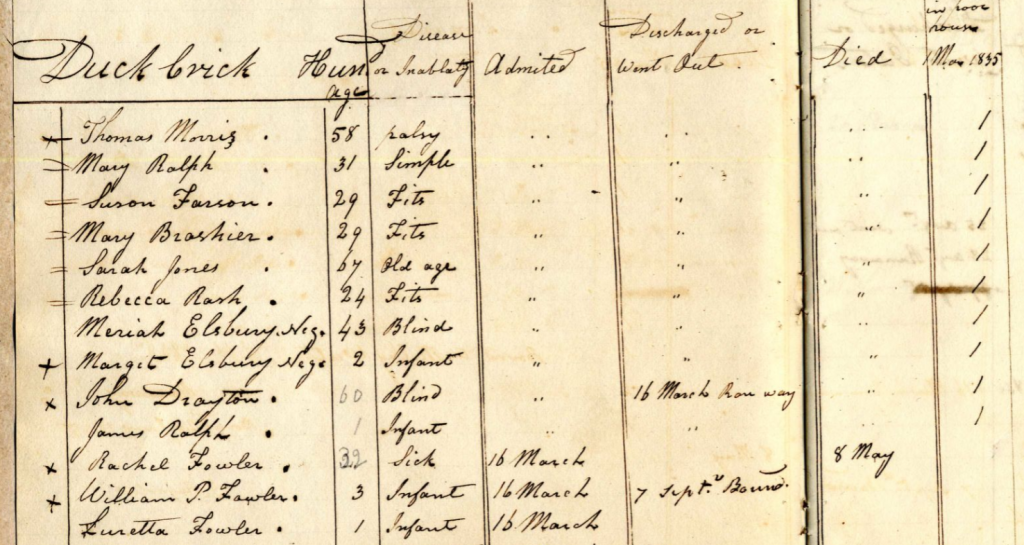

The sampler featured here was created by 12-year-old Louretta Downham. Louretta was born Louretta Fowler, and she spent her early years in the Kent County Alms-house, also called the “Poor house” at that time. She came to the house alongside a woman, Rachel, and boy, William. The woman passed away shortly after they arrived at the Alms House, and Louretta was given, at age 3 or 4, on June 5, 1837, to the Downham family.

She was given to the family with an indenture agreement, a common practice in that time. They were to teach her “housewifery” and take care of her until her 18th birthday. Upon reaching adulthood, the Downham family was to provide her with two garments of clothing to begin her life as an adult woman. Documents show that during this time she also worked for the Cooper family, where she made her sampler and whose descendants ultimately donated it to HCA’s collection.

Unfortunately, Louretta would not have the chance to reach adulthood. Records show she passed away in 1849 at age 15, but do not explain what happened.. Her memorial is in the Cooper Farm Cemetery in Kent County, and she is buried near Mr. And Mrs. Downham. Her gravestone states she was the adopted daughter of James Downham.

How did adoption work in the 1800s?

Louretta is described as adopted on her headstone, but the process of adoption in the 19th century was different from modern adoption, in part due to how childhood was viewed at the time and in part because laws governing the adoption of children only began to be passed in the middle of the 19th century. Children were seen as contributing members of a household who did their part to work for the family in whatever way was needed. An unrelated child brought into a home for care would be expected to work, just as the natural children of the family were.

Many genealogists and researchers have run into the complex system of 19th century adoptions. How close an adopted child was with the family who took them in varied. Whether they were listed as a child, employee or servant depended on the individual family, as did whether the child was still seen as part of their adopted family after reaching adulthood.

The conditions under which Louretta went to live with the Downhams bear similarities with today’s adoptions in that she was a child in need of care, and it was through an agency that she was given to a family that was able to provide that care. However, the Kent County Trustees of the Poor, the agency that was caring for Louretta before she went to the Downham family, sent her there as an indentured servant. This was common practice for the time in Kent County, Delaware.

Indentured servitude is the contractual agreement to work without pay in exchange for something. It ranged from conditions that were, for all extents and purposes, enslavement, as opposed to more truly mutually beneficial experiences, such as apprenticeships. It does appear that Louretta’s case was more like the latter.

How did HCA find this information?

Many people who lived and died long before us have left very little record of their lives. As a child, born in poverty, an indentured servant, a woman, and who died young, Louretta’s life fits many of the reasons as to why so little is known. The uneven social values for those like her, as well as for minorities, immigrants, and people with mental illness, contribute to the lack of records, images and personal items left behind. While the Cooper family kept her one remaining creation, there was so much more to her than this sampler. Sadly, those additional intimate details of what Louretta’s life truly was like are likely lost to history.

In many cases, the only knowledge historians have of an individual’s life story comes from records made by others. Legal documents, institutional data and receipts can describe where and when things happened to people. The process of trying to uncover Louretta’s life began with a family story and an indenture document.

Unravelling Louretta’s story

Upon donating her sampler, the family informed HCA that it was made by a girl who had worked as a servant for their family.

Her indenture agreement, which resides with Delaware Public Archives, provides her birth name of Fowler and her connection to the Trustees of the Poor. Through the Trustees of the Poor, HCA’s Curator of Historic Collections Katy Little was able to locate the year Louretta arrived at the alms-house and the names of two other Fowlers who arrived the same day as her: Rachel Fowler, age 39 at the time, and William P. Fowler, who was two years older than Louretta. Although no familial connections were recorded on the document, it is very likely that Rachel is her birth mother, and William is her older brother.

Rachel passed away shortly after she and the children arrived at the alms house and both Louretta and William were bound to go out to new families. Louretta to the Downham family, and William to John Reynolds, although William’s indenture states that Mr. Downham later took William in as well. William has no memorial in the cemetery with the Downhams and Louretta. It is unknown by state historians at this time what became of him.

Historic documents also can be full of small inconsistencies. Louretta’s name on early documents is spelled “Luretta.” Her tombstone states she was adopted, while the legal paperwork shows that of an indentured servant. These small discrepancies can be significant when searching for a paper trail and require historians to think outside of the box at times.

Despite remaining questions and so few personal belongings, it is only through extensive record-keeping, and a little detective work, that modern-day historians can piece together unique, individual stories in this way.

Louretta’s short time on this earth has not been forgotten, and we honor her memory today.