The Green Book: Acclaimed guide included Delaware locations for travelers of color

Just a few generations ago, travel for people of color could be nothing short of perilous. While racism continues to challenge American lives, racially driven hardships during the Jim Crow era and even following the Civil Rights movement meant African Americans had to carefully consider the businesses they’d frequent, and even where it was safe to stop for gas or rest while traveling. Even famous African Americans traveling to work as performers encountered dangers as a result of segregation and racism in the states.

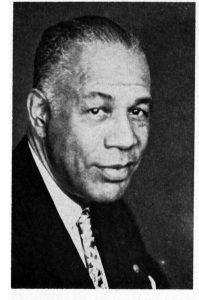

Beginning in 1936, African Americans turned to a publication that would guide them safely to enjoy vacation destinations and other stops during travel, thanks to author and publisher Victor Hugo Green. The guide, initially known as “The Negro Motorist GreenBook: An International Travel Guide” (commonly known as The Green Book) was published yearly, starting with listings in the New York metro area and northern New Jersey, until about 1964. About 15,000 copies per year were produced. The guide included listings for hotels, restaurants, gas stations and tourist homes, but was not an exhaustive list, as businesses had to pay a fee to be advertised.

The guide’s coverage area expanded over the years, encompassing Delaware locales by the late 1930s. It became so popular that it eventually included listings in Bermuda, Mexico and Canada. making it an international publication. Green’s wife Alma took over as editor after he retired in 1952. Green Books could be found at Esso Gas Stations, owned by Standard Oil (later known as Exxon), a company that welcomed African American francisees.

In early 2015, the Delaware Division of Historical and Cultural Affairs launched a research project to examine the Delaware Green Book and compile a listing of underrepresented African American cultural resources still in existence. The project, conducted by Historian Carlton Hall, examined two editions of The Green Book, from 1949 and 1956. Hall has given extensive presentations on the project to the public, with the next one slated for the Coastal-Georgetown Branch of the American Association of University Women on Feb. 16, 2023. Check back soon for more information on that event!

“Delaware businesses listed in The Green Book made accommodations for African Americans during segregation years. The history of these Delaware properties and property owners represents little known African American history in the state of Delaware,” Hall wrote in the study. “The properties researched are interesting examples of people of color acquiring land and establishing businesses during and after the Great Depression. The history of these owners show that they were business owners that broke stereotypes as tax-paying business owners.”

The 1949 Delaware edition listed 17 properties — including hotels, restaurants, barber shops, beauty parlors, tourist homes, a nightclub, a service station and a garage. Ten of Delaware’s listings were in Wilmington, three hotels were listed in Dover and Townsend offered a hotel and a garage. Sussex County had only three listings, all located in Laurel. Only 12 properties were included in the 1956 edition.

“The most popular Green Book listing in Delaware was the Rodney Hotel located along DuPont Highway near Townsend in southern New Castle County, which was in operation from 1947 until 1965 when it was destroyed by fire,” Hall explained.

Another familiar spot, first listed in the vacation section of the 1952 edition, was Rosedale Beach, which was part of the “Chitlin Circuit” and attracted well-known performers including Aretha Franklin, Sam Cooke, Ray Charles, James Brown and Stevie Wonder, Hall said. He noted in his study that more research on these locations is needed. Meanwhile, the Division is actively working to compile more historical information on Delaware’s segregated beaches during the Jim Crow era through the Segregated Sands research project and exhibit.

“I think it’s important for people to think about how life was, and what people of color born from 1928-1945 had to go through to travel,” said Hall. “It wasn’t as easy as putting in gas and going to a hotel. Some hotels didn’t take African Americans because they didn’t have to, and that’s the way it was back then. People had to sleep on the side of the road in a car and pack meals because they couldn’t just stop and rest.”