Collection close-up: 20th century snapshot

By Carolanne Deal, inclusive history researcher

At the Division of Historical and Cultural Affairs, the collections staff is invested in studying material culture, a term used to describe the art and objects created by humans. Until recently, like many cultural institutions, the material culture of marginalized groups was preserved disproportionately and has been under-researched at the Division. To correct past shortcomings and share a fuller vision of Delaware’s rich history, the curatorial staff has made changes in the daily collection practices.

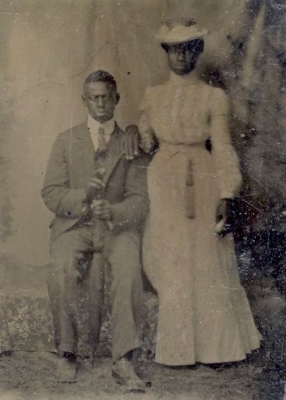

One of my recent research projects encompassed a photograph of an African American couple from the turn of the twentieth century in the division’s Historic Collection. Although the image is not dated, the subjects’ clothing indicate that it is likely that this photograph is over 100 years old, making it a valuable object in the collection. Through ancestry research and visual analysis of the photograph, I was able to infer an approximate year the photograph was taken: 1900. My analysis also led me to construct a biography of the people portrayed in the image.

This photograph shows Georgetown, Delaware, residents George H. Ingram (1860-1910) and Nicey A. Ingram (1864-1948). Census records show that George Ingram was born a year before the Civil War to free African American parents in Georgetown, and Nicey Ingram’s parents were also free natives of Georgetown. A Sussex County marriage certificate shows they were married in June 1885 and had four children: Ernest (b. 1886), Bertie (b. 1888), Rebecca (b.1894), and Mary (1896-1989). From 1890 to 1920, the couple and their family lived in rented houses in Georgetown.

Census records also reveal that Ernest, Bertie, Rebecca and Mary Ingram all learned to read and write. At least one of the Ingram children attended Georgetown Colored School, as evidenced by another photograph in the historic collection which depicts Mary Ingram’s school class in 1906. Mary is seventh from the left in the back row, and a small “x” was drawn on the photograph over her head. At the turn of the 20th century, Delaware did not have a statewide school system for Black children, nor did they allocate sufficient public funds to the existing schools. Most schooling for African American children occurred in one-room buildings like the one depicted in this image. In 1923, Pierre S. du Pont generated funds for a new school to be built for the area, which later became known as the Richard Allen School, a site now on the National Register of Historic Places.

George Ingram worked as a farm laborer in Georgetown before dying in 1910 at the age of 50. Nicey Ingram worked as a housekeeper and laundress in Sussex County. After the death of her husband, she lived with her children, Rebecca and Mary, and grandchildren, Ernest (1910-1972), George (1913-1993), Francis (b.1916) and James (1919-1997), in Georgetown, before passing away at age 84 in 1948. Although exact biographical information about the Ingrams does not exist, there’s a story to be found by examining how the couple presents themselves in this portrait.

While portraiture was initially reserved exclusively for the upper class, the invention of photography in the 1830s allowed portraiture to become accessible to people of all classes by the late 19th century. The portrait of George and Nicey Ingram is a kind of photograph called a tintype which means the image was produced on a thin sheet of iron. Popularized during the Civil War, tintypes were an inexpensive photographic medium used well into the 20th century. For two cents or less, individuals could pay a photographer to produce a small (3.5-by-2.5 inch) image to take home. Many of these types of photographs were taken in a photographer’s studio, like in this photograph evidenced by the plain, draped background behind the couple. Tintypes are considered “direct positives” because they make one-of-a-kind images without the use of a traditional negative. By examining the small details in this portrait, we can discern how the Ingrams wanted to represent themselves.

It is often assumed that African Americans in the late 19th century wore out-of-style clothing because they could not afford or had no interest in fashionable attire, however, this photograph proves that to be false. Fashion in the 19th century evolved rapidly, and African Americans participated in mainstream trends which can be seen in the fashion of this portrait.

George Ingram’s hair is closely cropped, and he wears a suit jacket, dress shirt, tie and detachable collar. The single-breasted jacket worn with a black tie was introduced in the 1880s and became a popular choice for working-class men in the decades that followed. His clothing, therefore, is entirely on trend for men at the end of the 19th century.

Nicey Ingram, on the other hand, rests her right hand on his shoulder, and holds an unknown object in her left hand. Her hair is fashioned in a pompadour style with a white hat on top. The pompadour hairstyle reached peak popularity in the 1890s and continued to be worn by women into the 20th century. She could be wearing a two-piece dress, or a shirtwaist style blouse and skirt. The shirtwaist was an article of clothing introduced to women’s fashion in the 1860s and designed to “look like a man’s shirt.” The shoulders of her garment are subdued, in comparison to earlier “leg-o-mutton” sleeves, which indicates a 1900 date for this photograph. Additionally, her lower sleeves are in the bishop style which was also popularized in the early 1900s. A hand-fan, a common accessory at the time, hangs from her belt.

The details in this portrait demonstrate that African Americans, despite economic, political and social disenfranchisement, utilized fashion to express themselves and assert their affluence. Although the Historic Collection does not have personal items belonging to the Ingrams, this image documents they valued staying up to date on fashion trends, and either had the finances to purchase these clothes or were skilled and could make them by hand. Unfortunately, African American clothing from this period mostly was not preserved for study, so photographs like these serve as a record for African American fashion and history.

Inclusive History Researcher Carolanne Deal is working to highlight the stories often relegated to the margins of history and making those stories accessible to the public. She holds a bachelor’s degree in art history and a master’s degree in art history for museum professionals, both from the University of Delaware.