Beach-going in Delaware: Black perspectives under segregation

By Kelli Racine Barnes, exhibit design summer intern, Zwaanendael Museum

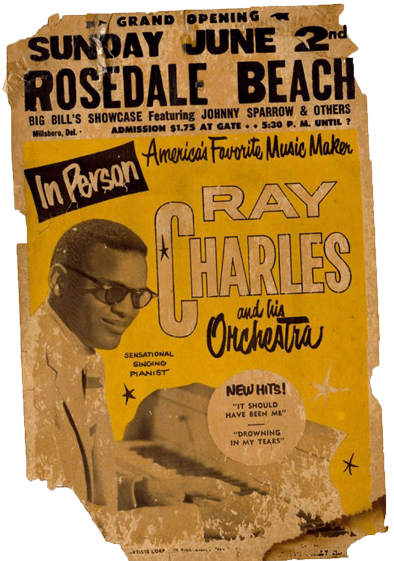

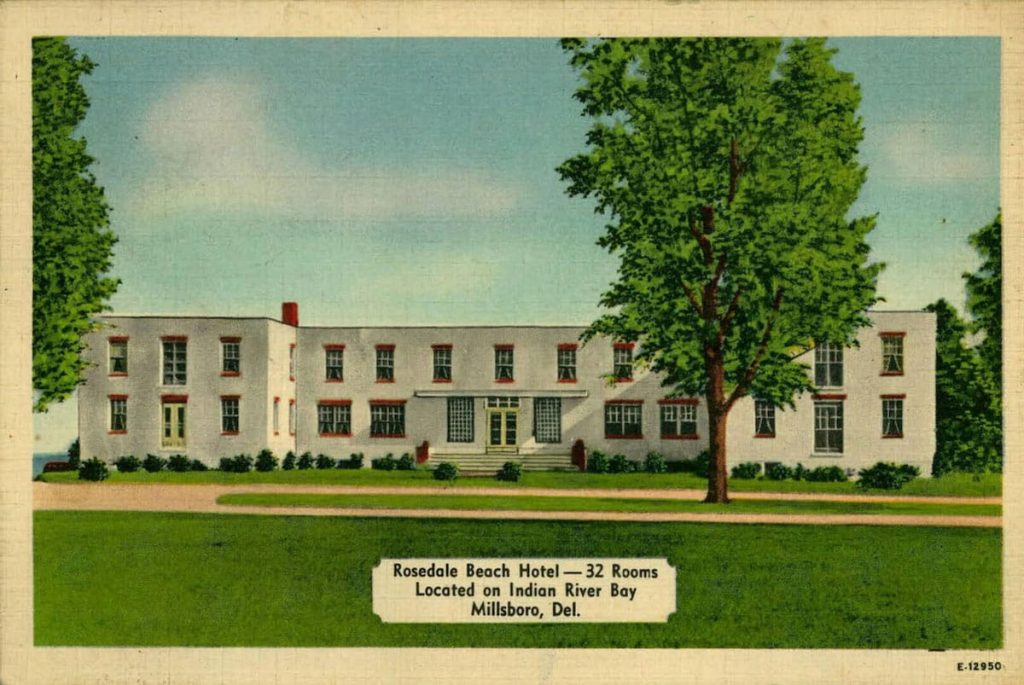

On Sunday, June 2, 1957, Ray Charles and his orchestra appeared at the Rosedale Beach Hotel and Resort in Millsboro, Delaware where they performed several of their hits including “It Should Have Been Me” and “Drowning in My Tears.” This was one of many events held at the resort since it was established in 1937 for the pleasure of Black, Indigenous and other people of color seeking entertainment and refuge during Jim Crow segregation in the United States.

Rosedale Beach was one of only a few beaches in Delaware where people of color could enjoy leisure activities. This was because, by the early-20th century, Delaware government officials systematically repressed Black, Indigenous and other residents of color through state sanctioned laws of segregation which extended to all facets of life including recreation. After the Civil War, the Delaware General Assembly rejected measures of equality enacted by the federal government including Reconstruction, the Civil Rights Bill of 1866, the 14th Amendment and the 15th Amendment. Segregation laws became the norm, determining how Black people engaged with Delaware’s beaches. Because this history and people of color’s perspectives on this history have been so understudied, little is known about this part of Delaware’s larger story.

During the summer of 2021, as a virtual E. Stewart Lyman Fellow and exhibit design intern at the Zwaanendael Museum in Lewes, Delaware, I was given the opportunity to create a digital exhibit centering the Black American experience of beach-going in Delaware. Growing up in a family that loved to attend the beaches of New Jersey, I was thrilled with the opportunity to uncover the Black experience and perspectives of beachgoers in the state of Delaware. We were particularly interested in the early-20th-century Jim Crow segregation era. With few elders left in our communities who remember this time and can share their perspectives with us, the time to learn about this history through first-hand accounts is right now!

I began with a set of research questions and goals to guide me through the exhibit-design process. I wanted to know how many segregated beaches existed in the state of Delaware under Jim Crow; what Indigenous people owned, and remained caretakers of, the land; who owned the land of each of the beaches prior to their being designated as beaches for Black people to congregate; what happened to the beaches after integration following the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964; and were the beaches featured in the travel guides, posters, or in the white or Black newspapers of the era?

I began this internship with an introduction to Rosedale Beach. I even visited the site where the resort once stood. It was a peaceful experience to be in the space that was beloved by so many people of color in the early-20th century. I could imagine the excitement that people would have had coming to this location to see their friends and family, to hear world class music and eat delicious food without having to worry about answering to the whims of white people’s needs or insecurities. I could imagine the calmness that may have washed over them while on the beach looking out over the still waters of the Indian River.

By the end of the internship, I had compiled a list of 12 locations where Black people recreated under Jim Crow in Delaware. Rosedale Beach is the most well-known of these locations because it was a summer venue for the Chitlin’ Circuit and a safe location where Black travelers could visit and feel welcome. Several of the other beaches, such as Woodland Beach and Bowers Beach, had designated days in which the owners of the land allowed people of color to visit. Others, such as Rehoboth Beach and Lewes Beach, had sections of their beaches, sometimes partitioned off, where people of color could visit for their opportunity of fun in the sun. You have to wonder how segregationists explained the need for a partition on the beach when everyone swam in the same body of water!

Rosedale Beach is all the more significant because the land was owned by members of the Nanticoke Indian community well into the 20th century. Subsequently, land lots were purchased by Black real estate entrepreneur, Jesse Walter Vause and his wife, Geoffie M., as well as Jesse’s cousin, Floyd Vause and his wife, Gussie Mae. They incorporated and established the Rosedale Beach Hotel and Resort on April 16, 1937. In oral history interviews that I conducted in 2021, local residents Robert Draine and Charles Laws recalled entertainers such as Ella Fitzgerald, Duke Ellington, Ray Charles, James Brown and the young Stevie Wonder performing at Rosedale Beach in the 1950s and 60s.

Rosedale Beach is the only beach in Delaware that I know of with this legacy of ownership and musical history. There is still so much to learn about the history of music, and also religion or spirituality, at these beaches. Many of the beaches began as church meeting sites, including Rosedale Beach which was enjoyed by the Nanticoke people for religious and recreational purposes prior to the land being purchased by the Vauses. Furthermore, many Nanticoke people remain in the area to this day as caretakers of their ancestral homeland. Further north, the Lenape Indian Tribe of Delaware remains as caretaker of its ancestral homeland as well.

I am extremely grateful for learning this history about the traditional stewards, caretakers and developers of Delaware land and its waters. It is a long, complicated history encompassing the Nanticoke and Lenape people, white European settlers, enslaved Africans and freed African American people that settled in the area. I learned a great deal about Delaware’s beaches from Black and white newspapers of the 20th century; oral histories and news reports that were conducted about the beaches of Delaware; travel guides published in the early-20th century for Black travelers; resources given to me by local historical societies; and several secondary sources about the Nanticoke and Lenape people, the white European settlers who colonized the land that became known as Delaware, and the history of Black land ownership along United States southern shores. The Delaware Public Archives was a great source for general images of the beaches. Unfortunately, none of the images I found featured positive representations of Black beach goers, only white beach goers. I am also grateful to my elders who allowed me the opportunity to speak with them this summer about my project and their recollections of visiting the beaches of Delaware under Jim Crow segregation laws.

This summer’s research builds on the work of Tamara Hall who researched and was instrumental in the Nov. 15, 2011 installation of the historical marker at Rosedale Beach. I am also grateful for the research of Sterling Street, Robert Draine Sr. and WRDE-TV Chief Meteorologist Paul Williams who researched the history of Rosedale Beach; Carlton Hall who has concentrated on sites featured in the travel guides; and Nancy Alexander at the Rehoboth Beach Museum who began an oral history program to learn more about the history of Rehoboth Beach, and about Rosedale Beach and other sites Black people established during the era. Now, with my internship complete, I look forward to seeing the published digital exhibit at the end of the year. It will be a glorious time to celebrate its publication and the 10th anniversary of the installation of the historical marker at Rosedale Beach!

Kelli Racine Barnes is a doctoral candidate at the University of Delaware studying late-18th- and early-19th-century African American history. In addition to being honored by the university as an African American Public Humanities Fellow, she was named an E. Lyman Stewart Intern for the summer of 2021. Barnes’ research on beaches open to African Americans during the segregation era will form the core of the digital exhibit “Segregated Sands: Beach-going in Jim Crow Era Delaware” that will be launched in 2022.